Marketing Channels and Logistics: A Case Study of Pepsi International.

Introduction

When a company enters a foreign market, the distribution strategy and channel it uses are keys to its success in the market, as well as market know-how and customer knowledge and understanding (Bellhouse and Hutchison, 1993; Ilonen,et al., 2011). Because an effective distribution strategy under efficient supply-chain management opens doors for attaining competitive advantage and strong brand equity in the market, it is a component of the marketing mix that cannot be ignored (Bowersox and Morash, 1989). The distribution strategy and the channel design have to be right the first time (Daugherty, 2011; Layton, 2011). The case study of Pepsi International provides evidence of the situation that a company faces when its distribution strategy in the international supply-chain management is, in fact, ineffective and not right!

Pepsi Cola International accessed the Ukrainian market via exports back in 1968 and since then has been trying to sustain its position in the market. It exports its concentrate, via routes to the country that are interchanged every now and then, to 12 local bottling companies who then sell it to distributors, who then deliver it to retail stores. Despite the fact that the supply-chain management has led Pepsi to gain local fame and popularity, it is inefficient in terms of cost which reduces the ability of the company to earn higher profits (Menachof, 2001). The discrepancies in demand and supply, conflicts between channel members, the environmental impact and theft along the way seriously harm the company’s profitability. With Cola Cola entering the market, Pepsi needs to redefine and redesign its supply-chain strategy to meet the challenges faced in the market and sustain its position in the country. These challenges are discussed in detail to provide possible solutions for the company to improve its supply chain and marketing channels in the light of existing literature, theories and models of marketing channels and logistics.

Task 1

CHALLENGE 1: GAPS IN DEMAND AND SUPPLY

One of the two big challenges faced by Pepsi is the gap in supply and demand. This is mainly a result of Pepsi’s lack of presence in the market and its heavy reliance on outsourced distribution. Gaps in demand exist in the supply chain when the company fails to meet the demand via distribution. The delivery of irregular quantities produces this gap (Bowersox and Cooper, 1992). Gaps in supply exist due to the channel members’ lack of expertise in the distribution process. Efficient supply-chain management has been widely advocated in the literature on marketing channels and logistics (Wetzels, et al., 1995; Harvey and Novicevic, 2002; Minuj and Sahin, 2011; and Rollins, et al., 2011).

Evidence that there is an efficient and effective supply-chain strategy comes from customer satisfaction and the quality of customer service provided. In the case of Pepsi Cola International, an entire rural segment of customers is excluded from distribution, which shows the lack of focus given to customer service in the supply chain. As much as Pepsi Cola International would like to blame the local distributors for this, the main responsibility lies on its own head for developing a distribution strategy without proper consideration of the customer segments that exist in the country and for not hiring managers to control the supply-chain operations in the country, who would have inculcated efficiency in the supply chain (Menachof, 2001).

Pepsi Cola International has two consumer segments in the Ukraine that have not been segmented properly. So far, Pepsi’s focus has been on the urban consumers. This case study highlights the growing demand for Pepsi in the rural areas (Menachof, 2001), which is not surprising as recent studies of the developing economies of the world have found that the largest and fastest growing customer segment is rural populations. However, their variable income and therefore their purchasing power is different from that of the urban consumers. This results in marketers generally ignoring the rural population and focusing mainly on urban consumers, as Pepsi is doing in the Ukraine. There is immense geographic dispersion and this, together with lack of proper infrastructure, prevents big companies from establishing tailored marketing channels to target these customers. Ignoring the rural consumers may be a disaster for Pepsi in terms of losing out on access to a larger market share in the country.

CHALLENGE 2: CHANNEL CONFLICT

Channel conflict is another big challenge faced by Pepsi Cola International in the Ukraine. It is the result of the high level of interdependence in the supply chain between different parties and channels and the lack of power and control exercised by Pepsi Cola International in the supply chain. All power has been given to the locals which has inculcated inefficiencies in providing quality customer service and reaching all customers as desired by Pepsi (Menachof, 2001). The main source of this conflict is the cultural difference between the local distributors and the Pepsi Cola International’s country of origin.

The locals have the mindset and approach towards business whereby they allow themselves to practice any form of legal or illegal practice that may enable them to earn short-term and quick profits, regardless of their commitments to their suppliers (Menachof, 2001). They have the same approach towards Pepsi. With Pepsi outsourcing the entire supply-chain operation to locals, the locals feel free to assume their own business philosophies and execution methods as they hold no fear of disappointing their supplier. Without power and control from the vertical chain, the distributors are free to deliver as they please, regardless whether they meet marketing targets. This is a challenge; it is partly the result of carelessness on the part of Pepsi for outsourcing the supply chain entirely and showing no sign of taking authority and control of any part of the marketing channel.

While Pepsi Cola International’s management is used to independence in decision-making in marketing strategies and plans, in the Ukraine it has refused to tailor its strategies to meet the local challenges and has completely given up all control of everything that the locals take over (Menachof, 2001). It is, without doubt, a failure on its part to give away power and control that needs to be positioned in the supply-chain management of the company.

The supply chain is most vulnerable to economic, social and external impacts. The challenges faced by Pepsi in the Ukraine are common to multinationals when they enter developing countries. According to Svensson (2002), there is a high level of vulnerability in the supply chains due to various interdependencies between the channels and parties within the supply chain that inculcate issues of power and control. Also, channel conflicts, channel coordination and relationships between the channels can create a level of vulnerability. About 90 per cent of the challenges faced by Pepsi Cola International in its marketing channels in the Ukraine are related to the relationships between the channel members. The main cause of vulnerability in marketing channels, as identified by Svensson (2002), is due to the relationship dependencies. These need to be in the control of the company in order to avoid any existing and potential threats.

CHALLENGE 3: ENVIRONMENTAL IMPACTS

The case study has identified that the infrastructure also poses a challenge for Pepsi with regard to effective distribution and increased transit times. This has both time and cost implications and therefore contributes further towards inefficiency in the overall supply-chain management of Pepsi Cola International in the Ukraine. The roads are of poor quality and traffic is very leniently managed which adds to the complexity of- and difficulty in managing routes. The distributors mainly use roads to distribute the product to the stores. Where the pickup time from the bottlers can be managed and monitored, the delivery time is hardly ever followed as per schedule, due to the problems caused partly by the infrastructure and partly by the carelessness of the distributors. It is the distributors who pick up the final product from the bottlers and take it to the stores where customers can purchase the bottles for consumption (Menachof, 2001).

As regards bringing in the concentrate from the port to the bottlers, Pepsi Cola International has to ensure care at any cost. Therefore, it prefers to use rail travel for this. However, during winter the concentrate tends to freeze, making it useless for consumption. This adds to costs for the company and further reduces the efficiency of the supply chain (Menachof, 2001). There is no other way to deal with the matter. Pepsi has not brought in its own specialised vehicles that could ensure the safety and security of the concentrate. It has chosen to rely on the vehicles of the bottlers and the distributors, which has only produced further challenges for the company.

CHALLENGE 4: THEFT

Theft is a common problem in the Ukraine which has weak law enforcement and the multinational companies operating in the country are not spared from this threat. The concentrate that is shipped in is most vulnerable to theft at the port. For this reason, PCI has to deploy security staff to make sure the concentrate reaches the bottlers safely (Menachof, 2001) which adds to costs in the supply chain. Further, this does not fully ensure the safety of the concentrate and the company still has to accept that on a regular basis some of the concentrate will be stolen from the port or on its way to the bottlers. The loss itself creates a cost burden for the company. The distributors also face the threat of theft, but locals are much more immune to this and know how to deal with it. The foreigners are the ones most affected by local theft.

Task 2

Supply chains are the most vulnerable to economic impacts and in times of economic downturn, companies have to make sure that their supply chains are altered and managed to cope with the challenges. It has been found that the supply chain adds up to 80 per cent of the cost that is passed on to the customer from the producer. In this regard, improvement in performance and efficiencies are key factors in a supply chain that enables the company to earn profits (Salciuviene et al., 2011).

The main source of problems for Pepsi Cola International is its heavy reliance upon local companies in its supply chain which has resulted in lack of effective and efficient performance. The strategy that will allow it to deal with the challenges is to install its own plants in the country, as Coca Cola has done. It needs to step into the market permanently, bring in its formula and operations and not just use outsourced distribution to penetrate in the market. The implication of this strategy is that each of the conflicts and challenges that Pepsi is facing in the Ukrainian market will be resolved. Gaps in demand and supply and channel conflicts are two big challenges that contribute the most to the current inefficiencies in distribution. Environmental impacts can be easily curbed once the company decides to step into in the market. This is discussed in detail later.

SOLUTION 1: REDUCING DEMAND AND SUPPLY GAPS

An effective distribution strategy is one that is designed and tailored according to the customer segment. Pepsi Cola International needs to tailor its distribution to meet the demands of the rural consumers. It first needs to segment its market for the two types of customers: rural and urban. According to Craig and Douglas (2011), despite of the fact that the rural consumer market has a low capital income that shrinks its buying power, the market has great potential due to the size of its population as a percentage of the total population. With the growing awareness of the developments in the urban population, the rural consumers aspire to consume brands to improve their standard of living. This is a factor which provides local and multinational brands the easy means to penetrating the market using low-cost marketing models (Craig and Douglas, 2011). Coca Cola in Africa has penetrated African rural villages by installing its own refrigeration system in stores to provide consumers with cold drinks. It often delivers its product by hand to individual consumers to meet demand in the area. This is a lesson to be learned by Pepsi as, with Coca Cola now in the Ukrainian market, it is only a matter of time before that the brand will spread its wings into the rural market of the Ukraine as well. Pepsi Cola International, with the help of the local institutions and NGOs, can make efforts to install the necessary developments in infrastructure to allow more efficient distribution in the rural areas which will benefit it greatly in the long run.

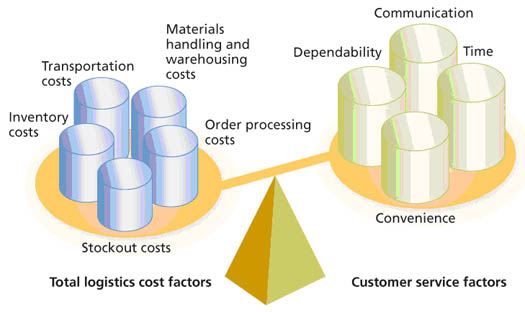

The biggest argument against this is the consideration of the costs involved. This brings in the need for effective supply-chain managers that Pepsi has completely ignored. Harvey and Novicevic (2002) deem effective supply-chain management to be highly important for balancing logistical cost factors and customer service factors. This balance is illustrated in Figure 1, shown below.

Figure 1: Balancing Logistical Cost Factors against Customer Service Factors

Pepsi Cola International, as well as bringing its operations to the country, needs to bring in expatriate supply-chain managers who are fully committed to- and deeply involved in the company’s marketing operations. It needs a strategy which focuses on customer quality and service; unlike the local distributors whose main concern is to make ends meet via short term profits (Wetzels, et al., 1995). This balance in the supply chain can only be maintained if in-company individuals are involved along with the local distributors and bottlers in executing the distribution. Rollins et al., (2011) indicate that inter-firm customer knowledge-sharing in logistics services is highly important in improving efficiency in the supply chain. Relying on expatriate managers will not by itself ensure efficiency in the supply chain when Pepsi decides to move here. It needs to make the best use of the knowledge that the locals have to offer via proper knowledge-sharing channels in order to avoid possible complexities in decision-making (Manuj and Sachin, 2011).

SOLUTION 2: REDUCING CHANNEL CONFLICT

In order to reduce channel conflict, relationship marketing needs to be exercised together with taking power and control away from the locals and giving it to the in-company supply chain managers. Relationship marketing plays a key role in inculcating efficiency in supply-chain management. Commitment and trust have been found to be useful tools for establishing healthy and positive relationships in the supply chain channels, according to Salciuviene, et al., (2011), Svensson (2001), Young and Wilkinson (1989) and Zhuang and Zhou (2004). Svensson (2001) argues that without a ‘synchronized trust chain,’ the marketing channels cannot work together effectively. This trust component is especially important in markets where is there is the threat of leakages of company information, breakage of company and industry rules and a high level of involvement in illegal procedures and methods of business operations. The local distributors in the Ukraine are open to all types of business practices, irrespective of whether they are legal or illegal or acceptable by the corporate policy and marketing strategy of Pepsi Cola International. This is one cause of conflict that can be resolved through building trust between the interdependent channels. How to build this kind of relationship with the locals is another dilemma.

Mehta et al., (2001) indicate another important aspect of relationship marketing that deals with this dilemma. They put into place components of trust and commitment in the relationships with the channel members in the foreign market together with complete control over the supply chain operations in the foreign markets. They stress that the cultural influences which cause channel conflicts can be curbed with a tailored leadership strategy that first seeks to help the local channel members gain confidence via trust-building activities and then resolves the conflicts that rise from the differences in viewpoints and approaches to marketing. Aligning all of the channel members in foreign markets where cultural and social differences create difficulties in working towards the same marketing goal is a challenge that leadership, with a key emphasis on relationism, can effectively resolve. Mutual understanding of the marketing objectives that has benefits for all parties involved has to be established (Paswan, et al., 2011). For this reason, it is important that from now on, Pepsi exercises complete control over the supply chain operations using its own expatriate supply-chain managers and using only those distributors that show signs of commitment and with whom trust can be built. It needs to screen out those distributors who have the potential to cause harm and who show fewer signs of commitment to the company. (Liao, et al., 2011). For those who show positive signs, the company needs to make the best use of relationship marketing, putting into place the important lessons learned from the benefits of trust, relationism, leadership and commitment for reducing channel conflict to the minimum.

SOLUTION 3: REDUCING ENVIRONMENTAL IMPACT

Improving the infrastructure is necessary if Pepsi is to facilitate the distribution and inculcate efficiency in the supply chain. It needs to develop shorter transit times and cost saving by using alternative transportation routes such as rail. This, however, cannot be undertaken without the involvement of the local government authorities. The case highlights the problem of red tape in the government’s approach to work and which limits the benefits that Pepsi can derive with the help of the government in this regard. Pepsi Cola International, with the help of the local institutions and NGOs, can make efforts to develop the necessary infrastructure to allow more efficient distribution in the rural areas. This will be of great benefit in the long run. This will become much easier and be more effective once Pepsi sets foot in the market by establishing its own plants in various locations across Ukraine. According to Craig and Douglas (2011), building network relationships with the NGOs for the purpose of improving infrastructure is the only route available for foreign companies looking to expand in a developing country. Being present in the market, it can gain the attention of the NGOs and local institutions and can build mutually beneficial relationships for the long term that can allow efficient supply-chain management for the company.

SOLUTION 4: REDUCING THEFT

Unless Pepsi Cola International’s management decides to personally catch the criminal themselves, the problem of theft cannot be resolved! However, it can be curbed by eliminating the channel that is most exposed to theft; the shipment of the concentrate to the bottlers. Once the company enters the market by installing its own plants, the concentrate will be locally produced, thus removing the marketing channel of shipping and the additional costs inculcated by the channel members involved in this process.

CONCLUSION

Marketing channels have been regarded as gatekeepers and important assets for the success and effectiveness of the marketing strategy of any company (Bowersox and Cooper, 1992; Bourlakis and Melewar, 2011). If Pepsi is to gain competitive advantage in the market, it needs to invest further in its supply-chain management. With the growing interest of companies in expanding overseas into foreign markets, emphasis in research has been placed upon global supply-chain management, where the notions of channel strategies, channel conflicts and channel designs have been drawing interest of both researchers and practitioners (Beresford et al., 2011). Pepsi needs to incorporate these concepts and tools into its marketing strategy in order to enable efficiency in supply-chain management. Its focus needs to be on customer satisfaction in the market and cost efficiency along with a leadership strategy that takes into account cultural gaps that are affecting its ability to reach all customers.

REFERENCES

Bellhouse, A.E., and Hutchison, G.E. (1993) ‘A Model for the Analysis of Distribution Channels’, Marketing Intelligence & Planning, Vol. 11 Iss: 11, pp.22 – 27

Beresford, A., Pettit, S., and Liu, Y. (2011) ‘Multimodal supply chains: iron ore from Australia to China’, Supply Chain Management: An International Journal, Vol. 16 Iss: 1, pp.32 – 42

Bourlakis, M., and Melewar, T.C. (2011) ‘Marketing perspectives of logistics service providers: Present and future research directions’, European Journal of Marketing, Vol. 45 Iss: 3, pp.300 – 310

Bowersox, D.J., and Morash, E.A. (1989) ‘The Integration of Marketing Flows in Channels of Distribution’, European Journal of Marketing, Vol. 23 Iss: 2, pp.58 – 67

Bowersox, D.J., Cooper, M.B., (1992) Strategic Marketing Channel Management. McGraw Hill Book Company.

Craig, S.C., and Douglas, S.P. (2011) ‘Empowering rural consumers in emerging markets’, International Journal of Emerging Markets, Vol. 6 Iss: 4, pp.382 – 393

Daugherty, P.J. (2011) ‘Review of logistics and supply chain relationship literature and suggested research agenda’, International Journal of Physical Distribution & Logistics Management, Vol. 41 Iss: 1, pp.16 – 31

Harvey, M., and Novicevic, M.M. (2002) ‘Selecting marketing managers to effectively control global channels of distribution’, International Marketing Review, Vol. 19 Iss: 5, pp.525 – 544

Ilonen, L., Wren, J., Gabrielsson, M., and Salimäki, M. (2011) ‘The role of branded retail in manufacturers’ international strategy’, International Journal of Retail & Distribution Management, Vol. 39 Iss: 6, pp.414 – 433

Layton, R.A. (2011) ‘Towards a theory of marketing systems’, European Journal of Marketing, Vol. 45 Iss: 1/2, pp.259 – 276

Liao, K., Marsillac, E., Johnson, E., and Liao, Y. (2011) ‘Global supply chain adaptations to improve financial performance: Supply base establishment and logistics integration’, Journal of Manufacturing Technology Management, Vol. 22 Iss: 2, pp.204 – 222

Manuj, I., and Sahin, F. (2011) ‘A model of supply chain and supply chain decision-making complexity’, International Journal of Physical Distribution & Logistics Management, Vol. 41 Iss: 5, pp.511 – 549

Mehta, R., Larsen, T., Rosenbloom, B., Mazur, J., and Polsa, P. (2001) ‘Leadership and cooperation in marketing channels: A comparative empirical analysis of the USA, Finland and Poland’, International Marketing Review, Vol. 18 Iss: 6, pp.633 – 667

Menachof, D. (2001) Pepsi Cola International: Distribution & Pricing Policy in the Ukraine [online] Accessed 1 November 2011 from <URL:http://www.businesscases.org>

Rollins, M., Pekkarinen, S., and Mehtala, M. (2011) ‘Inter-Firm Customer Knowledge Sharing in Logistics Services: an Empirical Study’, International Journal of Physical Distribution & Logistics Management, Vol. 41 Iss: 10

Paswan, A.K., Blankson, C., and Guzman, F. (2011) ‘Relationalism in marketing channels and marketing Strategy’, European Journal of Marketing, Vol. 45 Iss: 3, pp.311 – 333

Salciuviene, L., Reardon, J., and Auruskeviciene, V. (2011) ‘Antecedents of performance of multi-level channels in transitional economies’, Baltic Journal of Management, Vol. 6 Iss: 1, pp.89 – 104

Svensson, G. (2001) ‘Extending trust and mutual trust in business relationships towards a synchronised trust chain in marketing channels’, Management Decision, Vol. 39 Iss: 6, pp.431 – 440

Svensson, G. (2002) ‘Vulnerability scenarios in marketing channels’, Supply Chain Management: An International Journal, Vol. 7 Iss: 5, pp.322 – 333

Wetzels, M., Ruyter, K.D., Lemmink, J., and Koelemeijer, K. (1995) ‘Measuring customer service quality in international marketing channels: a multimethod approach’, Journal of Business & Industrial Marketing, Vol. 10 Iss: 5, pp.50 – 59

Young, L.C., and Wilkinson, I.F. (1989) ‘The Role of Trust and Co-operation in Marketing Channels: A Preliminary Study’, European Journal of Marketing, Vol. 23 Iss: 2, pp.109 – 122

Zhuang, G., and Zhou, N. (2004) ‘The relationship between power and dependence in marketing channels: A Chinese perspective’, European Journal of Marketing, Vol. 38 Iss: 5/6, pp.675 – 693