Promoting health in the community – mental health

The word health comes from the Old English word hael meaning ‘whole’, a term suggesting that health refers to a whole person (Naidoo and Wills, 2000). In a definition by the World Health Organisation (WHO), health has been defined as the state of complete physical, mental, and social well-being and not merely the absence of disease (WHO, 2010). In this very old definition (first stated in 1948) the mental and social dimensions of an individual are considered. Indeed, the ancient Greek and Roman civilisations marked history with proverbs such as ‘νους υγιής εν σώματι υγιή’ and ‘mens sana in corpore sano’, accordingly, meaning ‘a healthy mind in a healthy body’. Despite the ancient proverbs and the WHO definition, mental health does not come to one’s mind when the term ill is mentioned, nor are mental health problems considered a disease in the “acceptable” ranges. This stigma – mental health problems follow only HIV/AIDS in this respect (Roeloffs et al, 2003) – coupled with uncertainty or limited knowledge (mainly from the side of the general public) of the causes and available treatments for such conditions possibly interferes with health promotion. The value of epidemiology in health promotion will be unravelled in this essay in the context of the major issue that is schizophrenia.

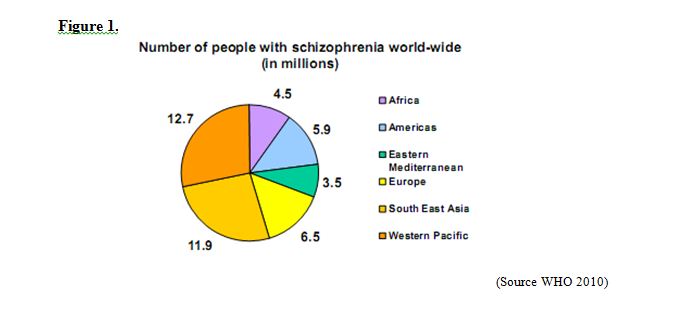

For the Department of Health (DoH), mental health problems such as schizophrenia are a priority along with other major disorders, such as heart disease and diabetes (DH, 2007). And not without reason since the WHO (2009) estimates that 50 million people in the world have schizophrenia (Figure 1). In the United Kingdom (UK), 1 in 6 adults has a mental health problem at any one time and more than 1 person in 4 will develop a mental disorder during his/her life (DH, 2009). The term schizophrenia (which comes from Greek words meaning “split mind”) was introduced to describe an illness in which ‘the personality loses its unity’ (Green, 2007). It has recently been stated that “schizophrenia is an end result of a complex interaction between thousands of genes and multiple environmental risk factors – none of which on their own causes schizophrenia” (Gilmore, 2010). These risk factors include genetic or inherited factors as well as environmental factors. Environmental risk factors include prenatal exposure to pathogens such as influenza (Brown et al, 2004), prenatal exposure to maternal stress (van Os and Selten 1998), obstetric complications (Cannon et al, 2002) and cannabis use during adolescence (Smit et al, 2004). According to the International Classification of Diseases (ICD), there are 99 distinct mental and behavioural disorders (block F20-F29), with schizophrenia being the most important member of the group consisting of 10 disorder entities (F20.0-F20.9) that include: paranoid, hebephrenic, catatonic, undifferentiated schizophrenia, post-schizophrenic depression, residual, simple, other and unspecified schizophrenia (WHO/DIMDI 1994/2006).

Schizophrenia is a debilitating chronic neuropsychiatric disorder which usually has an early onset in adolescence or early adulthood, mostly in the age group 15-35 (NHS, 2009). Schizophrenia is the most common form of psychotic disorder and according to the WHO schizophrenia is one of seven of the most disabling diseases in the age group between 20 and 45 (Leucht et al, 2007). One of the most substantial and significant attempts to draw the “epidemiological landscape” of schizophrenia at a global level has been done by Saha and colleagues (2005). By pulling together the findings of 200 studies from 46 nations, the authors examined the prevalence (point, period or lifetime prevalence) of schizophrenia and concluded the following: the median prevalence of schizophrenia is 4.6 per 1,000 of the general population for point prevalence (Table 1A), 3.3 per 1,000 of the general population for period prevalence (Table 1A), 4.0 for lifetime prevalence (Table 1A), and 7.2 for lifetime morbid risk (Table 1B). No significant differences could be observed between males and females, nor between urban, rural, and mixed sites, however it was concluded that migrants and homeless people had higher rates of schizophrenia. Finally, developing countries were found to have lower prevalence rates (Saha et al, 2005).

Across the UK the population prevalence of schizophrenia is somewhat similar to the global prevalence at 5 per 1000 in the age group 16–74 years, as stated by the National Survey of Psychiatric Morbidity (NHS, 2010). In the UK, both sexes seem to be affected equally by schizophrenia, the only difference being that the average age of onset is five years greater in women, with a second small incidence peak after the menopause (NHS, 2010). Furthermore and in line with the previously mentioned finding, individuals with schizophrenia tend to be unemployed and be receiving benefits from the state system. While, individuals from a black and ethnic minority background are more often diagnosed with schizophrenia, detained and treated compulsory under the Mental Health Act (1983). Last but not least, as stated in document available through the London Health Observatory (LHO), the prevalence of psychotic disorders such as schizophrenia increases 15 times in prisoners (LHO, 2010).

Several states of status (such economic, urban, migrant status) have been identified to influence the incident of this debilitating disorder and the following findings will be considered: studies have shown that those born in cities (i.e. urban environments) have an almost twofold increased risk of developing schizophrenia when compared to those born in rural areas. Furthermore, those living in cities have significantly higher incidence rates of schizophrenia compared to those living in mixed urban–rural sites (McGrath, 2008). It has been found that migrants have an increased risk of schizophrenia compared to that of native-born individuals. The UK-based Aetiology and Ethnicity in Schizophrenia and Other Psychoses (ΖSOP) multisite (Bristol, south-east London, and Nottingham) study found a nine-fold increase in the risk of developing schizophrenia in the black Afro-Caribbean population and also an increased risk in the South Asian population in the UK, when compared with the white British population. Specifically, the increased risk was 5.8 in black Africans and 1.4 in South Asians. (Pinto et al, 2008). Other studies have consistently found that individuals born in the winter and spring time have a small but significantly higher risk of developing schizophrenia. This later statement is one of the most repeatedly confirmed findings in schizophrenia epidemiology.

A further finding relates to work capacity or opportunities of. It is estimated that 30%-50% of people with schizophrenia are capable of work but only 10%-20% are actually in employment (Lelliot et al, 2008). The most alarming finding, however, is that individuals suffering from schizophrenia form a group with mortality rates twice as high as the general population (Leucht et al, 2007). As stated in a document provided by the LHO, the expected life expectancy of an individual with schizophrenia is 10 years less than someone without a mental health problem and that is due to the increased risk of premature death due to physical illness (LHO, 2010). Unfortunately, for individuals with serious mental health problems such as schizophrenia, access to quality medical care is problematic and that has been reported in several studies in the past decade (reviewed in Meyer and Nasrallah, 2009). These two final statements highlight the need for successful health promotion initiatives for schizophrenia, as currently those individuals are essentially deprived of their basic human right to work, but above all they are deprived of the chance to effectively lead a long healthy life.

To place the numbers and statements mentioned in the previous paragraph into context, schizophrenia is a serious mental illness that needs to be strategically addressed in order to reduce the burden of the disorder on the population. Epidemiological data are invaluable in providing incidence and prevalence rates that can then be addressed through better health service planning in order to achieve successful health promotion. Schizophrenia is a complex disorder that cannot be defined by one cause and the complex interplay of genetic and environmental factors that lead to this disorder creates a situation difficult to prevent. What can be improved though, and what epidemiology proves invaluable for, is looking at a wider picture and addressing those issues that cause increased prevalence. The reasons behind the increased incidence of the disorder according to urban, migrant or economic status need to be addressed. The reasons may be linked to social inclusion (in the case of migrants) or social status (in the case of homeless people) and health policies could be developed with these issues in mind.

Table 2. Prevalence of common mental health problems 2005

| Prevalence of common mental health problems by age, ethnicity and region (age group 16-74 years old) | ||||||||||

| Age Ethnicity Region | ||||||||||

White | Black | South Asian | Other | Northern and Yorkshire | West Midlands | North West | London | South East | ||

| Female | 19,4 | 19,2 | 17,8 | 22,9 | 24,9 | 18,0 | 17,2 | 25,2 | 22,4 | 16,3 |

| Male | 13,5 | 13,4 | 11,7 | 15,6 | 16,7 | 16,0 | 11,9 | 15,4 | 14,0 | 12,0 |

| All adults | 16,4 | 16,3 | 14,1 | 19,2 | 20,4 | 17,0 | 14,5 | 20,3 | 18,2 | 14,2 |

The above table and statistics agree with more recent findings in a report produced by the Royal College of Psychiatrists for the cross-government Health, Work and Well-being programme, in that compared with those who do not have a disorder, people aged 16 to 74 with a common mental disorder are more often women (59%), aged between 35 and 54. There are more people with mental health problems in areas of the country that have high levels of social and economic deprivation, such as the North West region of the UK and in deprived inner city areas (Lelliot et al, 2008). Modern Britain is characterised by inequalities in income and wealth and these lead to persistent inequalities in health (Naidoo and Wills 2001).

Another issue that needs to be addressed in addition to epidemiological data and factors related to illness is that of stigmatisation. Despite the fact that mental disorders are common, public awareness and knowledge is still not adequate (WHO, 2001). Social stigma refers to the unfair label that mentally ill individuals have been given by the general population, which may be irrelevant to the actual characteristics or behaviours of those affected by schizophrenia. Consequences of such stigmatisation may lead to barriers to housing or employment, restricted access to social services, increased mistreatment and even institutionalisation (Desjarlais et al, 1995). Moreover, this social stigma may be projected internally at the level of the affected individuals as a negative self-perception (Carling, 1995). This is a major challenge with regard to the integration of individuals with mental disorders into the community.

According to the Ottawa charter (1986), health promotion is “the process of enabling people to increase control over, and to improve, their health. To reach a state of complete physical, mental and social well-being, an individual or group must be able to identify and to realize aspirations, to satisfy needs, and to change or cope with the environment.” Health promotion policy requires the identification of obstacles to the adoption of healthy public policies in non-health sectors, and ways of removing them (Ottawa Charter, 1986). In the case of schizophrenia, it could be argued that stigmatisation and social exclusion form obstacles and therefore any health policy needs to take these two parameters into consideration. As stated by Stokols (1992) a “health promotive environment” is what is needed here. Stokols (1992) pointed out that “the majority of health promotion programs implemented in corporate and community settings have been focused on individuals rather than environments,” but there is need for programmes that “provide environmental resources and interventions that promote enhanced well-being among occupants of an area”. This is especially important in the case of schizophrenia.

Epidemiological data can steer the strategic guidelines for primary (prevent disease from occurring), secondary (early diagnosis & treatment) and tertiary (rehabilitation) prevention and the increased incidence status indicate areas that require closer attention. Primary prevention could include programs that are targeted towards groups those high incidence groups of migrants, the less advantaged economically and the inhabitants of inner city areas, with identified higher incidence and create health promoting environments. Primary prevention could also include programs, for instance, that promote healthier lifestyles through preventing substance use among those high-risk groups. Secondary prevention could be dealing with how to shorten the duration of schizophrenia, whilst the goal of tertiary prevention programmes should be to facilitate the inclusion or social cohesion of individuals affected by schizophrenia into their communities.

In conclusion, implementation of an effective health promotion as well as health care system for individuals suffering from schizophrenia is of enormous importance. With epidemiological data and identified factors that increase prevalence of the disorder as a guide, health promotion should have the central aim of ensuring full citizenship for people irrespective of their health status. Health policies should be specifically designed to target high risk groups, such as ethnic minority populations and the homeless. Health promotion should also aim to increase public awareness of mental health problems such as schizophrenia, and to reduce the social stigma in order to aid in the social inclusion of these individuals in their communities.

References

Brown, A.S. et al. (2004). Serologic evidence of prenatal influenza in the etiology of schizophrenia. Arch Gen Psychiatry; 61:774-780.

Cannon, M. et al (2002). Obstetric complications and schizophrenia: a historical and meta-analytic review. Am J Psychiatry; 159:1080-1092.

Carling P.J. (1995). Return to the community. Building support systems for people with psychiatric disabilities. New York, Guilford Press.

Department of Health (2007). On the state of Public Health Annual report of the Chief Medical Officer 2006.

Available at:

<URL:http://www.dh.gov.uk/en/Publicationsandstatistics/Publications/AnnualReports/DH_076817> [Accessed January 2010]

Department of Health (2009). Mental Health in the future – what do you think? Crown. New Horizons.

Desjarlais, R., Eisenberg, L., Good, B., et al. (1995). World Mental Health. Problems and Priorities in Low Income Countries. Oxford: University Press.

Gilmore, J.H. (2010). Understanding What Causes Schizophrenia: A Developmental Perspective. Editorial. Am J Psychiatry167:1.

Green, B. (2007). Schizophrenia.

Available at: <URL: http://www.priory.com/schizo.htm> [Accessed January 2010]

Lelliot, P. et al, (2008). Mental Health and Work. Working for Health.

Available at: URL:<http://www.workingforhealth.gov.uk/documents/mental-health-and-work.pdf> [Accessed February 2010]

Leucht, S. et al, (2007). Physical illness and schizophrenia: a review of the literature. Acta Phychiatrica Scandinavica; 116(5): 317-33.

LHO, 2010. Mental Health Prevalence.

Available at:

URL:<http://www.lho.org.uk/LHO_Topics/Health_Topics/Diseases/MentalHealthPrevalence.aspx> [Accessed February 2010]

Meyer, J.M. and Nasrallah, H.A. (2009). Medical Illness and Schizophrenia. Second Edition. American Psychiatric Publiching, Inc. pp 31.

McGrath, J. et al. (2008). The Epidemiology of Schizophrenia: A Concise Overview of Incidence, Prevalence, and Mortality.Epidemiologic Reviews; 30(1):67-76.

Naidoo, J. and Wills, J. (2000). Health promotion: foundations for practice. Second Edition. Elsevier Limited. Chapter 1.

NHS, 2009. Schizophrenia Annual Evidence Update 2009: Introduction http://www.library.nhs.uk/mentalHealth/ViewResource.aspx?resID=310231 [Accessed January 2010]

NHS, 2010. Schizophrenia Annual Evidence Update 2009: Incidence and Prevalence URL http://www.library.nhs.uk/mentalHealth/ViewResource.aspx?resID=311003 [Accessed February 2010]

Pinto, R. et al. (2008). Schizophrenia in black Caribbeans living in the UK: an exploration of underlying causes of the high incidence rate. Br J Gen Pract; 58:429–434.

Roeloffs, C., Sherbourne, C., Unutzer, J., Fink, A., Tang, L., & Wells, K.B. (2003) Stigma and depression among primary care patients. General Hospital Psychiatry; 25, 311-5.

Saha, S. et al. (2005). A Systematic Review of the Prevalence of Schizophrenia. PLoS Med 2(5): e141.

Stokols, D. (1992). Establishing and Maintaining Healthy Environments. Towards a Social Ecology of Health Promotion.American Psychologist; 47(1):6-22.

Smit, F. et al. (2004). Cannabis use and the risk of later schizophrenia: a review. Addiction; 99:425-430.

van Os, J. and Selten J.P. (1998). Prenatal exposure to maternal stress and subsequent schizophrenia: the May 1940 invasion of the Netherlands. Br J Psychiatry; 172:324-326.

WHO, 2010 (paragraph 1). Mental Health – WHO’s definition of health.

Available at: <URL: http://www.who.int/topics/mental_health/en/> [Accessed January 2010]

WHO, 2010 (figure 1). Schizophrenia – Facts

<URL: http://www.who.int/mip2001/files/1957/Schizophrenia.pdf>

[Accessed January 2010]

WHO, 2001. Mental Health in Europe. Country reports from the WHO European Network on Mental Health.

Available at: URL<http://www.euro.who.int/document/e76230.pdf>

[Accessed 29th January 2010]

WHO/DIMDI 1994/2006. Chapter V – Mental and behavioural disorders (F00-F99) – Schizophrenia, schizotypal and delusional disorders (F20-F29)

Available at:

URL<http://apps.who.int/classifications/apps/icd/icd10online/?gf20.htm+f20>

[Accessed January 2010]

Ottawa Charter, (1986). The Ottawa Charter for Health Promotion

URL<http://www.who.int/healthpromotion/conferences/previous/ottawa/en/>

[Accessed January 2010]