Organisational culture – Organisational structure and substructure; the impact on work groups and teams

Introduction

This essay attempts to critique the concept of the organisational culture (OC) and subculture and the effect that these have on work groups and teams.

Organisational culture, subculture and the impact on work groups and teams

Organisational culture offers a rich description of organisational life (Davies, 2002). Google, the trendsetting search engine company, has appointed a chief cultural officer whose main job is to maintain the company’s unique culture and to keep the ‘googlers’ happy (Mills, 2007). This unique company culture is identified by snack rooms packed with bins full of cereals, a café with outdoor seating to enable ‘sunshine daydreaming’, desks made of wooden doors mounted on two sawhorses, rituals like roller hockey matches every two weeks in the parking lot and routines like staff sharing spaces with dogs (Google, 2008). While these are the outward manifestations of Google’s culture, there is a deeper level which characterises the attitudes, beliefs and values of the organisation. These are essentially person- or support based (Handy, 1985) with the focus on a sense of belonging and support. organisational culture impacts the strategies, motivation levels and the structure of an organisation.

Schein (1996) describes organisational culture as being the most powerful and stable force in organisations. He studied the behaviour of prisoners of war (POW) in the Korean conflict and noticed that many prisoners had collaborated with the prison officers and had made totally unnecessary false confessions. He found that the captors had:

- manipulated information by not passing on supportive mail; telling one prisoner that the other had already confessed; and lecturing on their point of view

- manipulated incentives by rewarding those who cooperated, showing a tendency to confess, and punishing those who resisted

- manipulated group support by breaking up groups and removing leaders

- extracted confessions from the prisoners with complete sincerity

The captors had created a strong culture based on shared views and common experiences. Schein (1996) concluded that the zeal displayed by the prison officers, the creation of an environment by manipulation to create results and the shared belief system of the captors was responsible for breaking down some of the prisoners.

It would be useful to study the forces that create a culture (such as that displayed by the prison officers) and its influence on the management of an organisation, even though the goals of various organisations would be different. The culture of an organisation depends not only on its history but also the background and experiences of its members. Members of an organisation with a strong culture never actually question their beliefs or assumptions – they are taken for granted. Schein (1996) maintains that members of a culture are not even aware of their culture until they encounter one that is different from their own.

Organisational culture directly affects:

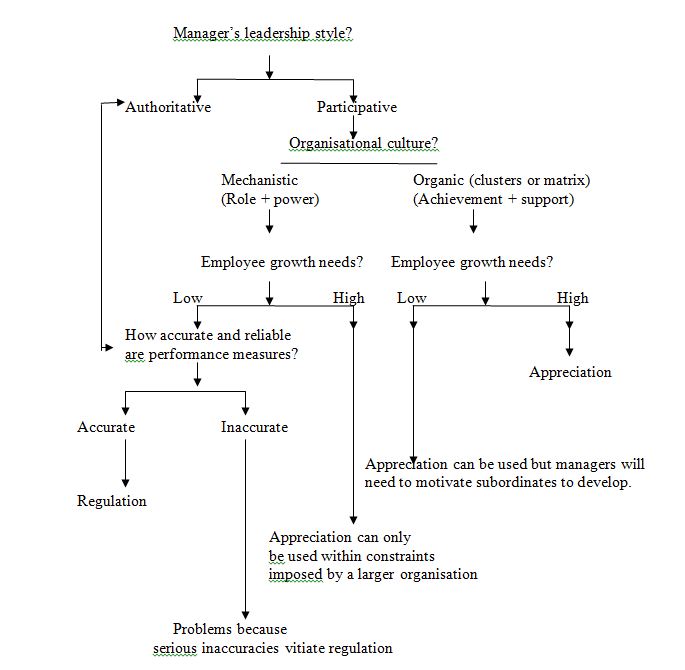

- the motivation of the employees – shown in Appendix One

- how organisations control, steer or overcome external or internal contingencies – shown in Appendix Two.

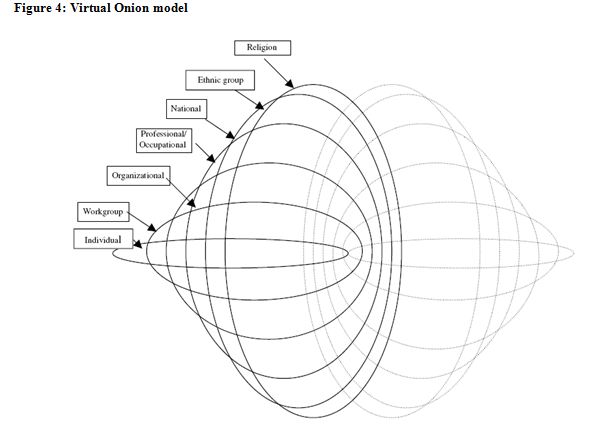

- Organisational structure and the organisational design – shown in Appendix Three.

Various researchers have categorised the different types of cultures that can occur in an organisation. Handy (1985) specified the power-role-task-person culture. Deal and Kennedy (1982) specified the tough guy, work hard/play hard, bet your company and process culture. Because it is difficult to order hierarchically the various facets of a culture, an abstract virtual onion model was introduced (Straub et al. 2002), which specifies that every individual has several layers (like an onion) of identity and experiences which can change, depending on time and circumstances. People also define themselves as being a member of the in-group or the out-group, depending on various factors. Therefore, according to the social-identity theory, culture cannot be classified as national or organisational but is made up of multiple levels which converge and interact for each individual, depending on various factors. A diagram of the virtual onion model is shown in Appendix Four.

Several researches have said that organisational subcultures can exist independently of the main culture and that each subculture has its own set of values, attitudes and beliefs (Brown, 1995; Martin, 1992; Martin and Siehl, 1983; Schneider, 1990; Sackman, 1991; Trice and Beyer, 1993 cited in Lok and Crawford (1999)). Lok and Crawford (1999) conducted a survey in hospital wards and found that there was a stronger commitment to a subculture (such as that found in the wards) than to the organisational culture (that of the hospital).

Schein (1996) has identified three such subcultures within current organisations – (1) the operator culture, comprising the workers and line managers whose main responsibility is to make and deliver products and services; (2) the engineer culture, comprising the technical people or designers in any organisation. The people within this subculture tend to believe in and rely more on technology and systems than on people. They believe that investing in relationships and building the trust of employees is expensive and largely unnecessary. Those within the operator subculture tend to feel threatened by the engineer subculture because they are given the impression that their roles are largely redundant and their jobs can be easily done by machines; (3) the executive subculture, comprising the CEOs, who generally view everything from the financial point of view because they have shareholders to answer to. Frequently, when people within the operator culture try to put forward proposals to, for example, invest in the training of the employees, the executives fail to act because they are reluctant to invest the required time, resources and money. They subconsciously collude with the engineers to give the human factor a low priority. Schein (1996) argues that only when each subculture spends time observing and absorbing the other subculture, learning to understand how different aspects of the organisation are affected, will an organisation truly mature.

Organisational culture also affects the behaviour of work groups and teams. Work groups are not necessarily teams – a team is a work group that has a personality of its own (Mannen et al, 1977). This is when members collaborate and assume an identity of their own as a unit.

Dornbush (1955), cited in Mannen et al. (1977, p39), said that in strict, regimental organisations like the army or the navy, a ‘union of sympathy’ develops among the recruits during the training programmes as a result of enforced regimentation. This is the case in, for example, the Coast Guard Academy. It often happens in bureaucratic organisations that one person acts as a mentor to a group or an individual and the behaviours and norms of that person get translated into a common culture across the group. Some organisations require stringent tests in order to gain entry: elite universities, professional sports teams, and military organisations are some examples. Such a culture bestows but also destroys individual identity.

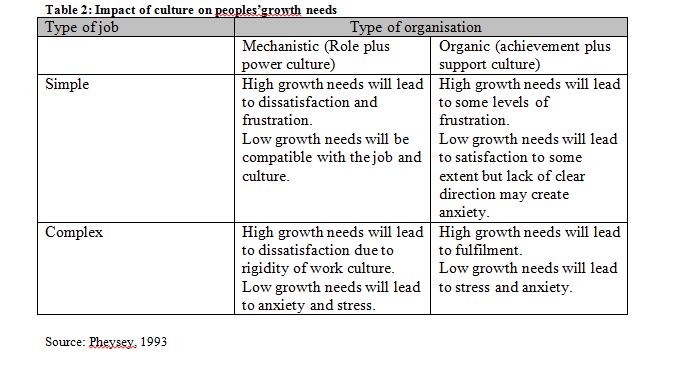

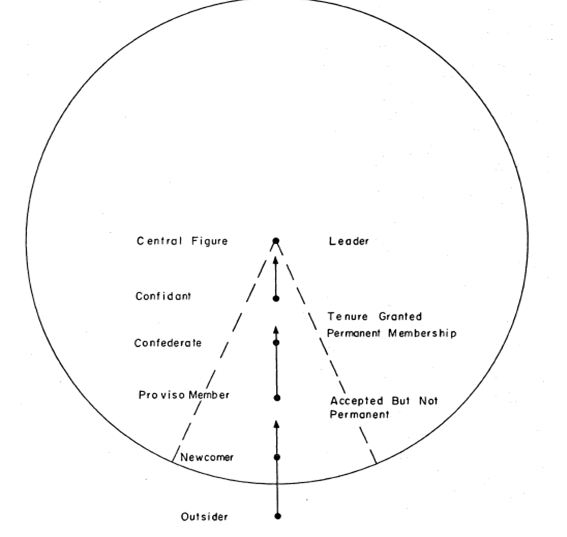

The relationship between agendas, groups and cultures is shown below.

Source: Adapted from Pheysey, 1993

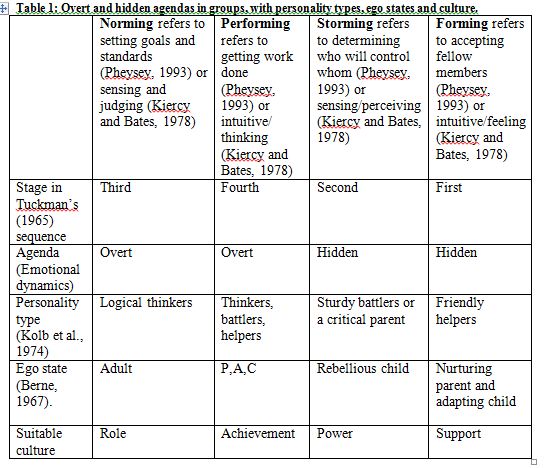

Hastings (1995) says that in new organisations, roles will emerge that will span boundaries and be more integrating.

Figure 1: Emerging roles in modern organisations:

Source: Hastings, 1995

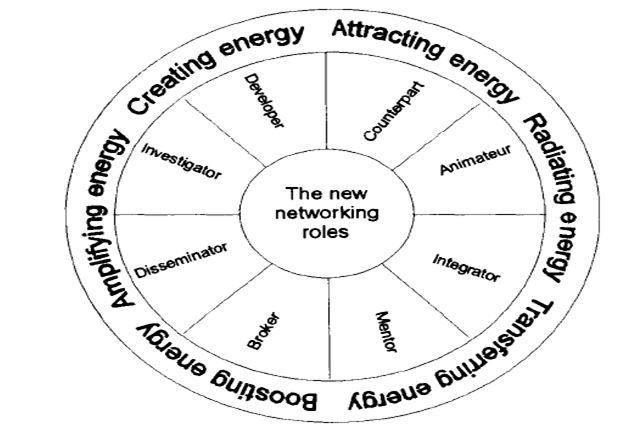

A new recruit to an organisation usually goes through a process of organisational socialisation (Mannen et al., 1977) where he/she acquires the culture of the organisation. Schein(1971), cited in Mannen et al. (1977), has stated that the relationship between a new recruit and others in an organisation may change, depending upon how much he/she identifies with the subculture of her/his group. Thus, a newcomer who is considered to be a good fit will move up the levels shown in the diagram below and will be accepted by the group. However, someone who does not fit in will always ‘remain on the edge’ (Mannen et al, 1977).

Figure 2: Inclusionary domains of organisations:

Source: Mannen et al, 1977

Conclusion

The impact and effect of the organisational culture and subculture should not be under-estimated. The organisational culture directly affects the strategies, motivation and the structure of organisations. It is important that managers accord organisational culture the importance that it deserves and this should be reflected in their recruitment practices. It is as important for a recruit to ‘fit’ into the organisation as to meet the other criteria that are considered for recruitment. As demonstrated by Schein in the POW study, an organisation that has a strong culture is capable of achieving things which may seem incomprehensible or impossible to others. At the same time, it is necessary for the subcultures to coexist harmoniously. The subcultures need to understand the other subcultures within the organization and consider the organisation as a whole. Only then will the organisation truly prosper. The success of an organisation will also depend on how well the work groups and teams work within the OC. ‘Organizational results are not simply the consequences of the work accomplished by people brought into the organization; rather, they are the consequences of the work these people accomplish after the organization itself has completed its work on them.’ (Mannen et al., 1977, p71)

Appendices

1. Impact of culture on peoples’ growth needs

2. Impact of culture on control strategy

Figure 3: A decision tree for choosing a control strategy

Source: Cammann and Nadler, 1976 cited in Pheysey, 1993

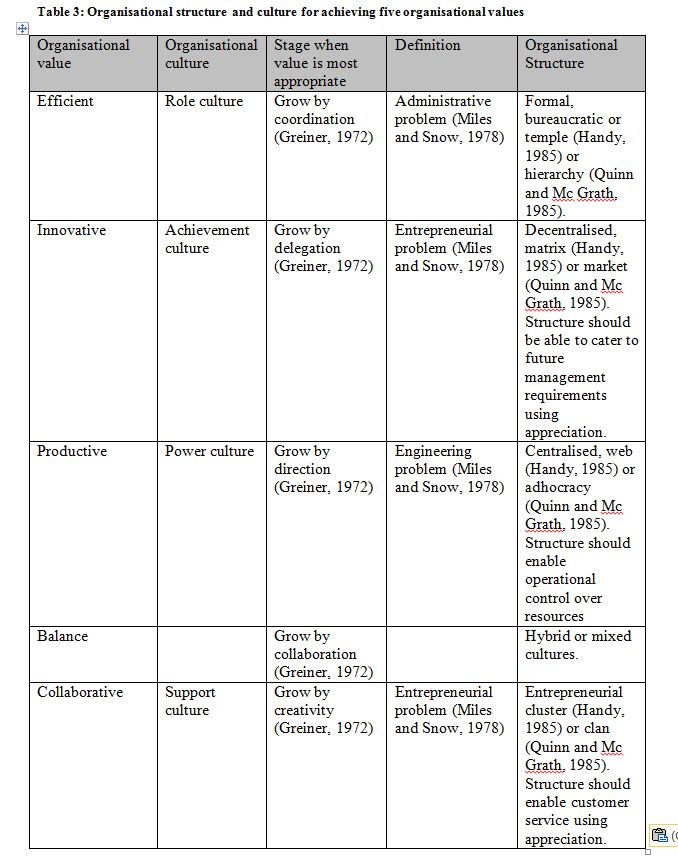

3. Impact of culture on structure and design of the Organisation

Table 3: Organisational structure and culture for achieving five organisational values

4. The Virtual Onion model

Source: Karahanna et al (2005) cited in Gallivan and Srite (2005)

References

Davies, H. (2002) Understanding Organizational culture in reforming the National health

service. Journal of the royal society of medicine [Online] vol. 93(3), p140-142 Available from: http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?artid=1279486#id2650016. [Accessed: 20 March 2008]

Gallivan, M and Srite. (2005). Information technology and culture: Identifying

fragmentary and holistic perspectives of culture. Information and organization [Online] vol. 15, p295-338 Available from: http://www.sciencedirect.com/science?_ob=ArticleURL&_udi=B6W7M-4FWKDVJ-1&_user=6368771&_coverDate=10%2F31%2F2005&_rdoc=1&_fmt=&_orig=search&_sort=d&view=c&_acct=C000033818&_version=1&_urlVersion=0&_userid=6368771&md5=afcfa383bb3b78081378e13f91c539c0 [Accessed: 20 March 2008]

Google (2008) The Google culture. [Online]. Available from: http://www.google.com/corporate/culture.html. [Accessed: 20 March 2008]

Hastings, C. (1995) Building the culture of organizational networking. Managing projects in new organizations. International Journal of project management [Online] vol. 13(4), p259-263 Available from: http://www.sciencedirect.com/science?_ob=ArticleURL&_udi=B6V9V-3Y44SFR-T&_user=6368771&_rdoc=1&_fmt=&_orig=search&_sort=d&view=c&_acct=C000033818&_version=1&_urlVersion=0&_userid=6368771&md5=bcc17da655eec47fee8e6f06e0f2fdde [Accessed: 21st March 2008]

Jana, R. (2007) HP’s cultural revolution. BusinessWeek, Nov 15. [Online]. Available

from: http://www.businessweek.com/innovate/content/nov2007/id20071114_289027.htm [Accessed: 20 March 2008]

Lok,P and Crawford. (1999) The relationship between commitment and organizational culture, subculture, leadership style and job satisfaction in organizational change and Development. Leadership and organization development journal [Online] vol. 20(7), p365-373 Available from: http://www.emeraldinsight.com/Insight/viewPDF.jsp?Filename=html/Output/Published/EmeraldFullTextArticle/Pdf/0220200704.pdf. [Accessed: 20 March 2008]

Mannen,V et al. (1977) Toward a theory of organizational socialization. MIT Alfred P.

Sloan school of Management [Online] vol. 960(77), Available from: http://hdl.handle.net/1721.1/1934 [Accessed: 22nd March 2008]

Mills, E. (2007) Meet Google’s culture czar. CNet News, Apr 27. [Online]. Available from: http://www.news.com/Meet-Googles-culture-czar/2008-1023_3-6179897.html [Accessed: 20 March 2008]

Pheysey, D. (1993) Organizational cultures. Types and Tranformations. London: Routledge.

Schein, E. (1996) Culture: The missing concept in organization studies. Administrative

Science Quarterly [Online] 41(2), p. 229-240 Available from: http://proquest.umi.com/pqdweb?index=0&did=9820938&SrchMode=1&sid=2&Fmt=6&VInst=PROD&VType=PQD&RQT=309&VName=PQD&TS=1206006584&clientId=28275 [Accessed: 20 March 2008]