Rebranding Marks and Spencer; the role of communication and the media.

MARKS & SPENCER (MEDIA THEORY)

Effective communication in everyday life depends on a need for the joint understanding of meaning which derives from actions between participants, on the basis of sending and receiving messages (Tarone, 1981; McQuail, 2010). People use communication to convey ideas, signs, and beliefs to interested individuals or audiences. Communication as a process is the platform on which relationships are built (Duncan & Moriarty, 1998), and building relationships is one of the most important goals for marketers and advertisers.

In integrated marketing strategies, communication is in the form of a promotional message and its main aim is to gain attention, to be understood, believed and remembered (Law, 2009). This communication process therefore aims at influencing, persuading and directly affecting the behaviour of target audiences (Schultz, 1993). But instead of just reaping the short-term benefits of persuasion, the desired aim of communication strategies is to effectively engage with audiences and build meaningful relationships, thus enhancing brand equity. Communication plays an important role in associating a brand with symbolic, functional, experiential benefits and attitudes based on each person’s frame of reference, culture and experiences with the brand (Keller, 1993). Touch points are therefore an integral part of communications strategies. The use of powerful and engaging media to interact with target audiences and the delivery of believable and memorable messages, associated with each person’s experiences of the brand in influential moments, are key components of creative marketing communication and campaigns (Shimp, 2010).

Mass media, the communication methods that are used for advertising, can be defined as the coordinated means of communicating openly with large audiences distant from each other, in a short space of time. It goes without saying that media are the driving force of everything that is happening around the world, by constantly re-shaping the structures of societies and cultures (McQuail, 2010). Mass-media consumption plays an important role in the forming of an individual’s personality, behaviour and attitudes by specifying a dimension of lifestyle (Hornik & Schlinger, 1981). The social categories that media vehicles form also affect people’s needs and wants, opinions and beliefs; interpretation of these categories in daily life can provide marketers with a blueprint of people’s consumption patterns and cultural ideologies (Traube, 1992; Hirschman & Thompson, 1997). Thus, the media play a significant role in how people comprehend and interpret meanings and messages.

A successful campaign needs to implement its key messages into the media landscape and understand audience characteristics such as attitude and cultural values which are shaping their behaviours. With the use of the four models of communication, the marketing communication strategy of M&S will be analysed to show how signs, symbols, cultural aspects, messages and meanings derived from the implementation of tactics boosted the company’s image and reputation.

Before the launch of the campaign, it was evident that M&S had lost its prestige and had become a fallen retail idol. Arrogance had led to non-existent communication with the City, alienating behaviour towards customers and a belief that advertising was unnecessary (Buxton, 1999). The brand image that M&S portrayed was that of an ailing organisation; a part of British culture that was fading away; a ‘grumpy, old brand’. As customers, journalists, and analysts had lost confidence in M&S, the main aim of the campaign was to regain the lost confidence and ‘give M&S back to its customers’, by returning to the traditional principles and values upon which M&S had been founded. Therefore, the communication required was to send a key message of the desire, commitment and confidence of M&S to change, accelerate awareness amongst its target audiences and change the brand’s perception by building positive impressions of M&S (Thompson, 2007).

M&S encapsulated the need for change in the ‘Your M&S’ slogan. It served as an acknowledgment of ownership of M&S by its public and was applicable to all products that are sold under the M&S brand. Also, it became a familiar slogan which was, and still is, applied to all audiences (Thompson, 2007).

Carey’s Ritual Model (1975) can give a clear explanation of the rationale behind the ‘Your M&S’ slogan and how it is linked to communication. By linking the slogan to all audiences, the campaign managed to communicate the belief that everyone participated in the change of M&S. The slogan celebrated a new era for M&S and unified people in order to become sentimentally involved with the brand again. Since audiences believed that M&S had lost its identity as a brand, its commitment to change the way it operated can be defined as a ‘representation of shared beliefs’ which, in this case, helped M&S to build and maintain relationships with its audience.

From the perspective of reception theory, ‘Your M&S’ managed to accommodate communication, partly because of the simplicity of its textual form. Discourse can be defined as the language which has been used to communicate something that is felt to be coherent (Cook, 1989). In this case, the coherent objective of ‘bringing M&S back to its customers’ needed to be summarised in a short, but simple message. Thus, ‘Your M&S’ was a simple statement that helped M&S to construct and deliver the meaning of ownership with its audiences. The flexibility and relevance of the slogan, which was applied to every product and product campaign, meant that it could be interpreted according to each customer’s frame of reference (McQuail, 2010). The main meaning of ownership was still intact, but each person could own M&S and relate it to his/her preference of products, decoding the right of ownership differently from others. For example:

- ‘In my M&S, I buy delicious food’

Or

- ‘In my M&S, I like to buy fancy clothes’

In a semiotic sense, ‘Your M&S’ can be seen as the perfect sign to illustrate M&S’s commitment to change; the simple language used in the slogan, and the contemporary and iconic design of it helped in this. By using the process of signification (de Saussure, 1915/1960; Barthes, 1967), the relationship of ‘Your M&S’ between the signifier (physical aspect) and the signified (mental aspect) can be described. People could hear or see that ‘Your M&S’ indicated a slogan for the company, but the associated meaning was that of an iconic British company which was changing its ways and was willing to give British people’s favourite shop back to them.

The media choices for this campaign underpinned the need for high visibility, frequency and reach. A choice of traditional mass media, such as TV, the press, and outdoor advertising were used to persuade people to regain confidence in M&S (Thompson, 2007).

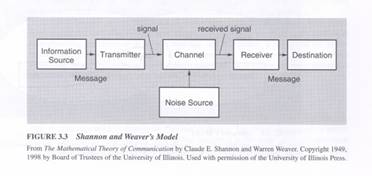

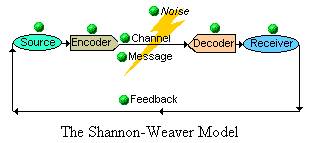

The media vehicles used to transfer the key meaning of confidence had to make an immediate impact on the audiences’ attitudes towards the brand. A one-way, linear and direct approach of communicating with audiences and transfer of information can be applied to describe media choices. The Shannon-Weaver Model (1949) can be used to explain the communication process; simple advertisements demonstrated confidence as a key message which was transmitted through video (TV) and image (the press, outdoor advertising) signals to audiences for processing. Media choices in this campaign allowed the message to reach high levels of efficiency, as audiences were ‘expecting the unexpected’ in the message conveyed in the communication process.

Picture 1: Shannon-Weaver Model (Shannon & Weaver, 1949)

Picture 1: Shannon-Weaver Model (Shannon & Weaver, 1949)

Intrusive broadcast, and unexpected, dynamic TV ads aimed to catch and hold the audiences’ attention in the campaign. In this case, message delivery was not the main aim, as high TV engagement during the run of the advertisements made audiences ‘enjoy the show’ first. Recognition of the ‘confidence’ element came secondary to TV spectatorship as part of the ‘media logic’ (Altheide & Snow, 1979).

The first appearance of the new brand idea which was summarised in the ‘Your M&S’ slogan was launched through a high-profile outdoor campaign. Clarity and simplicity of the slogan is essential to poster advertising, because it facilitates brand recognition, brand recall and attention (Gardner & Luchtenberg, 2000). This campaign also illustrated the new, more stylish line of clothing; more in line with the company’s changes at store level (Thompson, 2007).

The role of outdoor advertising in terms of communication can be explained by the publicity model. In order to attract attention, outdoor advertisements need to reach consumers when they are away from their homes (Shimp, 2010). This feature of outdoor advertising implies that communication exists only at the very moment that the attention-gaining process happens. Turning the attention of audiences to posters gave M&S the chance to send the first signs to them. New slogans and a range of new products were symbolic of the desire of M&S to change. Outdoor campaigns paved the way for brand recall and attention later in the campaign. The key concept of the new brand image was communicated successfully and enhanced brand recall and brand recognition, important factors in the success of an outdoor campaign (Donthu et al., 1993).

The lowering in M&S’s pricing strategy clearly highlights the importance of feedback in communication processes. By adding this factor to the Shannon-Weaver Model (1949), two-way communication can be achieved between the source and the receiver. In this case, feedback from the audience led to a rebuilding of the original message that M&S had transmitted. Communication research was needed to decode the information transmitted from the audiences’ negative attitude towards the value of clothes. Then, the new message was transmitted again in the form of print media advertising.

Picture 2: Shannon-Weaver Model Including Feedback

Picture 2: Shannon-Weaver Model Including Feedback

During this campaign, M&S had to remind people that M&S Food was still of high quality (Bussey, 2005). A food marketing campaign was implemented, with extraordinary results. Sales on the food category were increased, and the slogan of the advertisements ‘This is not just food; it is M&S food’ became a national catchphrase (Thompson, 2007).

The ‘M&S Food’ campaign became famous, thanks to the use of a set of semiotic codes and discourse language, embedded into the context of the advertisements, as well as from the role and the value of food in the society and culture. The signs that M&S used for the food campaign derive from what it stands for in the marketplace; that is quality, luxury, and iconic status within the retail sector (Burt & Sparks, 2002). These values, along with the food images, were added to the slogan ‘Not just food, M&S food’. Thus, the first thing that comes into people’s minds it that of a different, better kind of food. In the media frame which is used for the advertisements, M&S used various signifiers as well; the images of fresh and raw food materials; the luxurious furniture (image); the music soundtrack accompanied by the voiceover which builds a relationship with the receiver (sound) are some of the examples. The outcome for the receiver is the interpretation of ‘M&S Food’ as part of a high-status way of living which was derived from the social and cultural images shown (Tresidder, 2010).

The mixing of all signs and images through the media context led people to the final stage of the message interpretation. In this stage, people could escape from reality and become part of a fantasy which is associated with the consumption and the aesthetics of food along with memories or experiences from their social and cultural background. With the guidance of the medium (TV), which provides the time and space for the fantasy to occur, people could connote the ‘M&S Food’ experience as extraordinary, hedonistic, sacred and ritualistic. The media vehicles here allowed communication to illustrate an artistic representation of food advertising, which transformed the typical need for food consumption to an urge of relishing the majestic food experience that M&S promised.

Picture 3: ‘M&S food art’

Picture 3: ‘M&S food art’

After the success of the food campaign, and with confidence that women’s clothing was stylish enough to appeal to every woman, a new campaign was designed to show the new womenswear collection. M&S had to change women’s thoughts about its clothing lines; thus the recruitment of supermodels was the perfect way to portray the company’s confidence in the product. The campaign featured Twiggy, Britain’s most famous top model, in an attempt to parallel her comeback with M&S’s return to stardom (Thompson, 2007).

The campaign needed to convince women that they could now buy clothes without expecting to be disappointed. The role of the media was pretty clear; it had to produce a piece of work which could pass through all the links of the decision chain to become successful (Ryan & Peterson, 1982). Supermodels as ambassadors were a perfect choice from the media-logic perspective. Media consumption is celebrity-oriented, and an M&S advertisement which featured supermodels meant that it was able to attract and hold visual attention.

The comeback of Twiggy for the M&S campaign had a significant impact on its success. As a true national treasure and a symbol of the British culture, she became the driving force of this campaign. She was also able to get middle-aged women to relate to her (Kirby, 2005).

An explanation on the ‘Twiggy Effect’ and the success of the campaign can be linked, again, to semiotics. Supermodels, as signs, are the epitome of beauty and style, but linking them to M&S clothing seemed not to be enough. Twiggy’s role was crucial in this campaign; in a symbolic context, she was already a myth in the minds of British women. Her comeback connoted the element of nostalgia in women’s minds, especially in those who were close to Twiggy’s age and were familiar with her iconic status and her association with M&S during the sixties. Her appearance was a blast from the past, and by seeing her in the advertisements, women could make a temporal escape and bring back memories from their cultural conditions which probably involved interactions with M&S and clothing (Aden, 1995). Seeing Twiggy, stylish once again in M&S clothes, was a deciding factor in the persuasion process of communication, as it signified the return of M&S in people’s hearts. It can be seen as a perfect case of effective celebrity endorsement, because of the symbolic match which existed between Twiggy’s image and M&S’s image (McCracken, 1989).

Picture 4: The ‘Twiggy Effect’ – A blast from the past

Picture 4: The ‘Twiggy Effect’ – A blast from the past

The Christmas campaign, once again, showed a transmission in communication as it was essential to link M&S with the Christmas period. Most importantly, Christmas is a religious celebration, and so ritual communication was also significant. Associating the celebratory character of Christmas as a symbol of M&S’s clothing was very important for maintaining the relationship that had already been built.

The menswear campaign followed the same rationale as that of the womenswear. Communication was used to catch the attention of ordinary men. Here, the symbol of respect was very important in the decoding of meaning; seeing respectful men dressed in M&S clothes gave men the confidence to purchase the same clothes so that they could also feel respected and successful.

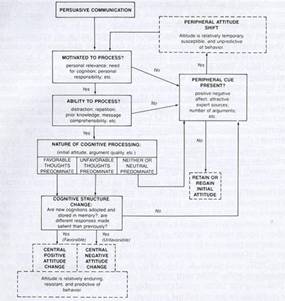

One of the core values of M&S is its ongoing commitment to ethical sourcing as part of the company’s defined responsibility to society (Tench & Yeomans, 2009). Again, communication was a process of display and attention, as the company needed to reinforce trust with those active members of the public who seek out information about the company’s environmental practices. It also wanted to make those latent or passive members of the public think about the issues. The elaboration-likelihood model (Petty & Cacioppo, 1986) can describe the rationale of this campaign. Active members of the public who thought about environmental issues were more likely to support M&S’s business practices by processing information centrally; passive and latent members of the public might be aroused by the persuasive communication (commitment to ethical sourcing), and try to form their own opinions about the matter, following the peripheral route.

Picture 5: ELM Model (Petty & Cacioppo, 1986)

Picture 5: ELM Model (Petty & Cacioppo, 1986)

M&S’s business practices can be related to the ritual model as well. Communication was linked to the company’s participation in the safety of the environment and it could be interpreted as a symbolic process whereby reality, in the case of ethical sourcing, is repaired (Carey, 1975).

The success of the campaign managed to turn around journalists’ negative impressions of previous years. Like any other target audience, they were stimulated by the continuous confidence and commitment of M&S to change. The role of communication was to attract the attention of journalists and make them interested in writing something about M&S. The power of the media used, especially TV, was enough to convince journalists to set an ‘M&S news-agenda’ (McQuail, 2010).

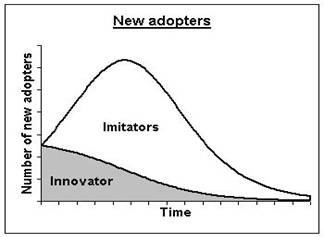

Word of mouth (WoM) played an important role in the adoption of ‘This is not just a…’ as a national catchphrase. Favourable associations with the particular slogan led to the creation of a ‘buzz’ effect, thanks to interpersonal, two-way communication between individuals (Shimp, 2010). Extended publicity generated this effect and helped the slogan to become a part of popular culture.

The enormous amount of PR coverage and WoM can be explained by using the Bass Diffusion Model (Bass, 1969). Journalists and individuals, who were first convinced about the change of M&S, became vocal supporters of the brand (innovators). Then, by acting as opinion leaders, they managed to get more and more people involved in the process. New adopters, who sprang from journalists, boosted news coverage whereas adopters of the slogan transformed it into a ‘sticky’ message with a national appeal.

Picture 6: Bass Diffusion Model (Bass, 1969)

Picture 6: Bass Diffusion Model (Bass, 1969)

To sum up, M&S managed to create a very successful ‘old-school’ campaign, based mostly on traditional media and classic persuasive communication processes. Vast broadcasting and simple forms of advertisements managed to transmit effectively the key message of confidence and commitment to change to large numbers of the target audiences.

What made this campaign so compelling though, is the way it helped people regain their trust and confidence. By involving all its customers, it communicated a national need to fight for a common cause: to make M&S the UK’s favourite retail shop once again. By using powerful signs and symbols within the advertisements, M&S reminded people why they had good reason to give the brand another try. The combination of powerful visual images, narratives and symbols of quality (food) and British popular culture (Twiggy) enabled people to associate their fantasies or memories with the brand and its products, which were more desirable than ever before. It persuaded customers to become more engaged with it because it was changing its arrogant manner and was listening to their needs. It managed to regain its iconic status and be a part of the British culture that people could feel happy about. M&S has managed to rise from the ashes and transform from being a ‘grumpy, old’ brand to a ‘stylish, modern’ one.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

- Aden, R.C. (1995) Nostalgic Communication as Temporal Escape: When it was a Game’s Re-Construction of a Baseball/Work Community, Western Journal of Communication, Vol. 59, Issue 1, pp. 20-38, [Online], Available from: http://www.informaworld.com/smpp/content~db=all~content=a912202953 [Assessed 11/05/2011]

- Altheide, D.L. & Snow, R.P. (1979) Media Logic, Beverly Hills, CA:Sage

- Barthes, R. (1967) Elements of Semiology, London: Cape

- Bass, F.M. (1969) A New Product Growth for Model Consumer Durables, Management Science, Vol. 15, No. 5, pp. 215-227, [Online], Available from: http://www.jstor.org/pss/2628128 [Assessed 10/05/2011]

- Burt, S. & Sparks, L. (2002) Corporate Branding, Retailing and Retail Internationalization, Corporate Reputation Review, Vol. 5, No. 2/3, pp. 237-254, [Online], Available from: http://itu.dk/~petermeldgaard/B12/lektion%206/Corporate%20Branding,%20Retailing,%20and%20Retail%20Internationalization.pdf [Assessed 10/05/2011]

- l%20Internationalization.pdf [Assessed 10/05/2011]

- Bussey, N. (2005) Has M&S Been Saved by Advertising?, Campaign (UK), Issue 47, November 18, [Online], Available from: http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=buh&AN=19205253&site=ehost-live [Assessed 07/05/2011]

- Buxton, P. (1999) Can Marketing Save Falling Retail Giants? , Marketing Week, January 28, [Online], Available from: http://www.marketingweek.co.uk/home/can-marketing-save-falling-retail-giants?/2031126.article [Assessed 08/05/2011]

- Carey, J.W. (1975) A Cultural Approach to Communication, Communication, Vol.2, pp. 1-22

- Cook, G. (1989) Discourse, Oxford: Oxford University Press

- de Saussure, F. (1915/1960) Course in General Linguistics, English trans., London: Owen

- Donthu, N., Cherian, J. & Bhargava, M. (1993) Factors Influencing Recall of Outdoor Advertising, Journal of Advertising Research, Vol.33, Issue 3, pp. 64-72, [Online], Available from: http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=buh&AN=9309136069&site=ehost-live [Assessed 10/05/2011]

- Duncan, T. & Moriarty, S.E. (1998) A Communication-Based Marketing Model for Managing Relationships, The Journal of Marketing, Vol. 62, No.2, pp. 1-13, [Online], Available from: http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=buh&AN=467985&site=ehost-live [Assessed 08/05/2011]

- Gardner, R. & Luchtenberg, S. (2000) Reference, image, text in German and Australian advertising posters, Journal of Pragmatics, Vol.32, No.12, pp. 1807-1821, [Online], Available from: http://www.ingentaconnect.com/content/els/03782166/2000/00000032/00000012/art00117 [Assessed 10/05/2011]

- Hirschman, E.C. & Thompson, C.J. (1997) Why Media Matter: Toward a Richer Understanding of Consumers’ Relationships with Advertising and Mass Media, Journal Of Advertising, Vol. 26, Issue 1, pp. 43-60, [Online], Available from: http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=buh&AN=9705213769&site=ehost-live [Assessed 07/05/2011]

- Hornik, J. & Schlinger, M. (1981) Allocation of Time to the Mass Media, Journal of Consumer Research, Vol.7, Issue 4, pp. 343-355, [Online], Available from: http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=buh&AN=4656582&site=ehost-live [Assessed 08/05/2011]

- Keller, K.L. (1993) Conceptualizing, Measuring, and Managing Customer-Based Brand Equity, Journal of Marketing, Vol. 57, No.1, pp. 1-22, [Online], Available from: http://faculty.bus.olemiss.edu/cnoble/650readings/Keller%20Brand%20equity%201993.pdf [Assessed 09/05/2011]

- Kirby, T. (2005) Twiggy: This Year’s Model. Again. , The Independent, October 12, [Online], Available from: http://www.independent.co.uk/news/uk/this-britain/twiggy-this-years-model-again-510583.html [Assessed 08/05/2011]

- Law, E.J. (2009) A Dictionary of Business and Management, Oxford University Press, Oxford Reference Online, [Online], Available from: http://www.oxfordreference.com/views/ENTRY.html?subview=Main&entry=t18.e1302 [Assessed 09/05/2011]

- McCracken, G. (1989) Who is the Celebrity Endorser? Cultural Foundation of the Endorsement Process, Journal of Consumer Research, Vol. 16, December, pp. 310-321

- McQuail, D. (2010) McQuail’s Mass Communication Theory, 6th Edition, London: Sage Publications Ltd.

- Petty, R.E. & Cacioppo, J.T. (1986) Communication & Persuasion : Control and Peripheral Routes to Attitude Change, New York: Springer-Verlag

- Ryan, J. & Peterson, R.A. (1982) The Product Image: The Fate of Creativity in Country Music Song Writing, in J.S. Ettema & D.C. Whitney (eds), Individuals in Mass Media Organisations, pp. 11-32, Beverly Hills, CA: Sage

- Schultz, D.E. (1993) Integrated Marketing Communications: Maybe Definition is in the Point of View, Marketing News, Vol. 27, No. 2, p. 17

- Shannon, C.E. & Weaver, W. (1949) A Mathematical Model of Communication, Urbana, IL: University of Illinois Press

- Tarone, E. (1981) Some Thoughts on the Notion of Communication Strategy, TESOL Quarterly, Vol. 15, No. 3, pp. 285-295, [Online], Available from: http://www.jstor.org/stable/3586754 [Assessed 07/05/2011]

- Tench, R. & Yeomans, L. (2009) Exploring Public Relations, 2nd edition. London: Pearson Education / FT Prentice Hall

- Thompson, M. (2007) Marks &Spencer, This is not just advertising this is Your M&S advertising: how confident communication helped restore public confidence in M&S, in Green L., (ed), Advertising Works 15, WARC, Henley-on-Thames, pp. 44-76

- Traube, E.G. (1992) Dreaming Identities: Class, Gender, and Generation in 1980’s Hollywood Movies, Boulder, CO: Westview Press

- Tresidder, R. (2010) Reading Food Marketing: The Semiotics of Marks & Spencer!?, International Journal of Sociology and Social Policy, Vol. 30, Issue 9/10, pp. 472 – 485, [Online], Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1108/01443331011072244 [Assessed 09/05/2011]