Essay on What Makes an Effective Teacher?

Number of words: 4017

Introduction

Being a teacher clearly entails more than being an instructor and helping pupils fulfill their educational potential. Teaching is a complex and multi-faceted area, one which is constantly evolving and is in a state of continual flux. In this assignment, the attributes which constitute an effective teacher will be disseminated, alongside a critical analysis of my own personal views and teaching ideology (primarily centred on creativity, adaptability and other such variables). The conclusions and points this assignment makes will be discussed with relevance towards my own practice. Recent and empirical literature will be consulted, in addition to a backlog of government reports and other such authoritative educational documents.

Furthermore, a critical appraisal will be evident throughout the course of this assignment, with the point that being an effective teacher may not just depend on one solitary attribute, indeed a plethora of traits need to be exuded in one’s practice for them to be deemed an effective teacher, particularly adaptability which is ever more pertinent in the educational climate that exists in the contemporary era. Although this assignment will adopt a general stance on what constitutes an effective teacher (not distinguishing particularly between educational levels), there will be some discussion (limited by the scope and wordage of this assignment) over the criteria which constitutes an effective teacher varies by the educational level (i.e. primary or secondary school) they are operating at.

The shifting ideals of education over time and their relevance towards being an effective teacher

Prior to discussing to a specific discussion over what makes an effective teacher, it seems apt to consider the issue from an empirical perspective and discern whether attitudes towards what constitutes an effective teacher vary over time or not. Intriguingly, Coe et al. (2014) noted that, in terms of teaching styles at least (in a study commissioned with the primary objective of discerning the optimum teaching style), little has changed over time, with ‘traditional’ (passive, rote learning and so forth) teaching methods being deemed to have a more tangible effect than new pedagogical methods which have been implemented recently (such as multi-sensory learning and other such initiatives and schemes) (DfE, 2010), indicating that in terms of pedagogical style espoused, little has changed in determining what constitutes an effective teacher. Whilst this point may be valid and relevant, in some aspects it disregards the other aspects of the dynamic and multi-faceted profession of being a teacher (or educator in any capacity), with (ironically), the teaching responsibilities of a practitioner no longer being the only attribute which is demanded of them in their teaching role.

Shuayb and O’Donnell (2008) note the changing attitudes towards education in the last 40 years- with a paradigm shift from focussing solely on the academic attainment of pupils (which is represented by the inauguration of the ’11 plus’ exam and the prevalence of grammar schools) towards educating the child as ‘a whole’ and focussing on a more ‘child centred’ method of education where their personal attributes are recognised in addition to their academic assets and potential. Whilst the aforementioned study may have been restricted towards formative (primary) education of children, the point that there is a more a ‘child-centred’ movement of education is applicable to all levels of the educational hierarchy (i.e. primary, secondary, tertiary and quaternary education). Ultimately, this movement is known as ‘holistic’ education (an ideology of education which had been pioneered empirically by notable individuals such as Rudolf Steiner and Maria Montessori) and has become commonplace in the educational movements accepted in the contemporary era. Rudge (2008) notes that ‘holistic’ education is an eclectic and dynamic paradigm which requires teachers to continually adapt their skills and account for the changes which have taken place in education, of which there have been an innumerable amount in the last decade (e.g. a move from modular to linear assessments; ICT being replaced with Computer Science; the difficulty of GCSE exams increasing and the amendments in the standards which qualified teachers must meet) (DfE, 2010; DfE, 2013).

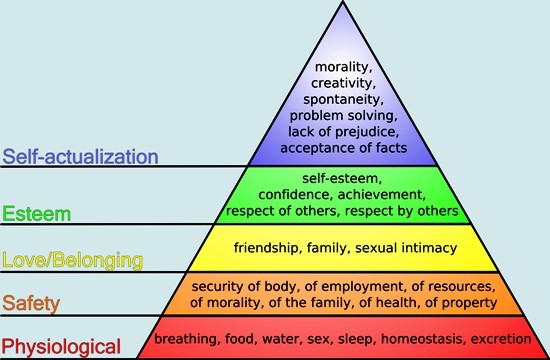

The child-centred nature of education (with an increased emphasis on recognising children as individuals and having their emotional needs met by learning) is illustrated by schemes such as Every Child Matters (DfE, 2004), SEAL (Social and Emotional Aspects of Learning) (DfES, 2005) and PLTS (Personal, Learning and Thinking Skills) (QCDA, 2011). Clearly, this illustrates how the child-centred approach (also known as ‘personalised’ learning) has become so prevalent in education today, which contrasts markedly with the academically-orientated curriculum which has been historically in evidence. Subsequently, referring back to the scope of the assignment, what makes an effective teacher has seemingly altered over time- now teachers are required to be much more than educators, being coaches, role models, mentors and in some cases even having to act in ‘loco parentis’ (assuming parental responsibilities in the school environment to compensate for a lack of familial support at home) (Patel, 2003). This implies that becoming an effective teacher in the contemporary era is a more challenging prospect than in the prior decades, primarily because of advances which have been made in this time in terms of understanding and knowledge. Ritzer (2007) defines the increased emphasis on the emotional and spiritual tenets (or purposes) of education as being the ‘informal’ curriculum in lessons which are delivered sub-consciously by the teacher such as how to behave appropriately and correctly and displaying respect and compassion towards others (particularly those of different cultures and faiths). Such needs could be potentially understood by studying Maslow’s (Dye et al., 2005) hierarchy of needs, which categorises the needs which people have according to their importance:

Figure 1: Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs (2004)

The ultimate goal in this theoretical model is individuals attaining the highest level in the hierarchy of ‘self- actualisation’ (in other words, fulfilling one’s potential), something which is the pinnacle in achievement of human life (Dye et al., 2005). Assuming the ‘deficiency’ needs (safety, physiological and love/belonging) are met at home or elsewhere for pupils, teachers could be responsible for propelling pupils to access the upper levels of the hierarchy, which seems to embody the holistic ethos of education referenced in the discussion above. The propensity and likelihood of teachers to achieve this may be affected by how influential they are. Riggio (2010) argues that the functions of teachers and leaders have a significant cross-over, with both being transformational (being capable of inspiring change amongst other individuals). Arguably, this may be easier for teachers rather than leaders to achieve as they are dealing with impressionable young minds, rather than adults who may have pre-conceived thoughts, behaviours and ideals. However, Maslow (Dye et al., 2005) also enunciates that only a minority (2%) of individuals are capable of attaining this landmark state of being, which perhaps devalues the impact that teachers can have, although displaying and possessing leadership qualities is clearly an integral component of being an effective teacher.

Clearly, being an effective teacher certainly entails both an awareness of the ‘informal’ (hidden) curriculum and an ability to demonstrate it in practice. This could be potentially attained by adhering to Bandura’s (1977) theoretical stipulations in that young children (i.e. pupils) are often influenced by the behaviours and attitudes of their caregivers or those adults who play a significant role in their lives. Bandura termed this phenomenon as ‘modelling’, which could be useful in assisting teachers in modelling the correct behaviours they wish to observe in pupils and enabling them to become effective teachers.

Upon the premise of this discussion above, the conjecture could be made that effective teachers need to be well-versed in the theoretical concepts surrounding education and how they can be applied in practice.

This assignment will now focus on the individual characteristics and dimensions of what makes an effective teacher, before reaching an eventual definitive conclusion over the attributes which an effective teacher possesses.

ICT and being technologically literate

One additional responsibility which teachers now have in comparison with the past to become an effective teacher is being technologically literate and display the capacity to integrate it effectively into their lessons, regardless of what subject they teach or what level they practice at. With the technological advances that have been made in recent years, Prensky (2001) speaks of the development of a group of people called ‘digital natives’ i.e. those who are used to residing with technology and it becoming an integral component of their daily lives (they could not imagine a life where technology was not at the forefront of their lives). This is seemingly accompanied by the assumption that teachers who are currently entering the profession automatically display some level of competency in technology, which seems to be reinforced by the abolishment of the ICT Qualified Teacher Status (QTS) skills test in 2012, in the sense that it seemed impractical to test prospective trainee teachers on a skill they were automatically assumed to possess in the digitally-dominated present era (DfE, 2012). This illustrates that being competent at technology is one attribute of being an effective teacher, even if it may not be the most important one.

Interestingly, ICT has been scrapped (and replaced with a new incarnation, Computer Science), with the requirement being that Teachers integrate ICT into every subject that they teach, in a cross-curricular modality of pedagogy which embraces the assets of technology (DfE, 2015). However, the conjecture could possibly be made that being a effective teacher involves more than simply being aware of how to integrate ICT within lessons. However, it must be conceded that it still takes considerable skill to effectively utilise ICT within a lesson, although it is the Government’s mandatory expectation that teachers do so in the contemporary era (DfE, 2015). Certainly, with the explosion of technology and the inundation of developments of it which have infiltrated the educational sphere, a teacher must be equipped with the sufficient skill to deploy it as a teaching vehicle effectively within a lesson or learning episode. Exemplifying this point in practice, Cogill (2008) notes that even with a seemingly simple piece of equipment such as an Interactive Whiteboard, a teacher must still have sufficient pedagogical assets to exploit its learning potential to the optimum.

In essence, in order to be an effective teacher (at least in the dimension of technology), a practitioner should possess the technical knowledge of using apparatus and the ability to incorporate it appropriately within a lesson.

Different models of pedagogy and accommodating different learning styles

Technology may be important in a teacher’s practice, but evidently being able to implement a cross-curricular style of pedagogy could also be assumed to contribute to being part of an effective teacher. Savage (2010) enunciates that cross-curricular teaching is a particularly good vehicle for pupils to engage in learning which stimulates them, particularly when it is performed in conjunction with their own learning experiences in life. The advantages of this to pupils’ learning experiences could be significant- Gazzaniga (2005) explains the split brain theory that has been in existence for over half a century, which states that individuals are either left brained (displaying a predilection towards logical subjects like Mathematics and Science where there is a definitive right answer) or ‘right’ brained (these types of individuals display a fondness for creative subjects like Art, English and Drama where the emphasis is more on expression, rather than the correct answer). However, if a practitioner were to teach in a cross-curricular manner (integrating more than one subject simultaneously into the lesson) then this may allow pupils to engage in ‘bilateral’ learning, where both sides (or hemispheres as they are known in the study of phrenology) are activated concurrently. An example of such integration within a lesson could be with English and Mathematics, subjects which are on opposing sides of the cognitive spectrum, (although Ofsted (2012) notes the increasing prevalence of worded questions in the mathematics curriculum, an assertion which is also confirmed in the content of GCSE Mathematics curricula (DfE, 2014), but could be linked to induce powerful and memorable learning experiences in the children.

Savage (2010) expounds that this connection can become even more relevant if pupils are taught in a way that is meaningful to them, i.e. connected with their real life experiences (therefore placing learning in a real-life context). Lave and Wenger (1991) term this to be ‘situated’ learning where pupils learn in a way that they can relate to their external experiences of daily life. Again though, it could be argued that a teacher would really have to possess significant assets to be able to do this proficiently, in terms of possessing the subject knowledge to be able to insert different subjects (in addition to their main specialism) within a lesson and also to have the pedagogical knowledge to utilise this appropriately. Indeed, the learning potential of cross-curricular learning could be to some extent negated by the spectrum of learning styles which exist in a classroom, a fact which is noted by empirical literature on a frequent basis.

Gardner (2004) promulgated a framework of multiple intelligence styles:

Figure 2- Gardner’s (2004) Framework of Multiple Intelligences

This in itself represents a challenge for a teacher in their quest to become effective due to the array of learning styles which are encompassed within a classroom, with pedagogy again an influential variable in determining the quality of teaching a practitioner espouses. To account for the varying learning styles of pupils within lessons, it could be theorised that a teacher should possess a sound knowledge of different styles in order to attain excellence in their teaching (and be an effective teacher). Mosston and Ashworth (2008) outlined a framework of teaching styles which range from teacher to pupil-centred (in terms of determining the amount of involvement from pupils within a lesson). Although these teaching styles were originally conceptualised for Physical Education (PE), they have since been extrapolated to the remainder of subjects within the curriculum. Yet again though, being aware of such theories is not enough to be able to become an effective teacher, which is a similar point to how subject content knowledge may not be sufficient alone in order to become an effective teacher (with pedagogical knowledge having to be present to act as a complement to it). Weick (1988) notes this process of relating learning and knowledge to practice to be known as ‘enactment’, something which an effective teacher should be able to do proficiently and at will.

In essence, it could be surmised that alongside possessing the triumvirate of sound pedagogical knowledge, an awareness of the teaching strategies at their disposal and the variance of learning styles in their class, a effective teacher must also be flexible in their practice, ensuring that they can tailor their teaching strategies to meet the needs of pupils within their class, in an approach which is reminiscent of a personalised style of learning, a commodity which is highly prized in contemporary education and deemed to be more effective than its apposite counterpart, an individualised learning style (QCDA, 2011).

Reflection and Creativity

Flexibility could potentially be assumed with creativity, which could be another facet in the armoury of skills an effective teacher must possess. Although the assumption could be made that creativity exuded by a practitioner requires spontaneity and an ‘innate’ teaching ability, the opposite seems to be true. Indeed, NCTM (2013) points out that creative teaching tends to require a significant amount of planning, as would any other teaching approach. It seems important to clarify here that creativity should not only be equated with spontaneity, but with logical and sound planning. In order to exploit the benefits of creative teaching (and become an effective teacher), reflection on one’s practice (in any area, such as aptitude in managing behaviour management or honestly appraising their own subject knowledge) may be needed. Schön (1983) is a staunch proponent of the importance of reflection in any profession, although it could be assumed to be particularly pertinent in an occupation such as teaching, which is a dynamic environment which is continually changing (as mentioned in a previous juncture of this assignment). Applying this principle specifically to the teaching domain, Pollard (2008) is also erudite and comprehensive about the importance of reflection in a teacher’s practice, philosophising that it can allow teachers to retrospectively consider their practice and think how they would act if similar events were to arise in the future (such as behaviour management or other aspects of teaching). Clearly the creativity which an effective teacher must display must also be complemented (or tempered, depending on the vantage point which one takes) by a degree of reflection and more than a quorum of planning to substantiate this creativity. Rubio (2009) supplements this discussion, articulating that a teacher must be reflective, innovative and flexible in order to be successful, particularly in response to changing school environments.

Particularly in the challenging nature of the 21st century classroom, creativity may be an important asset to possess, in an era where learning is becoming more personalised and matched to pupils’ expectations, rather than conforming to a ‘one size fits all’ model.

Conclusion

In essence, being an effective teacher cannot be classified by a singular set of prescribed attributes. Clearly there is more to being an effective teacher than displaying exemplary subject knowledge, as there are other assets which may be conducive to suitable practice in the field. An awareness of how creativity impacts upon pupils’ learning experiences evidently needs to be possessed for a teacher to be effective. Innovative practice may also be something that a teacher may have to display if they want to demonstrate commendable practice. Subject knowledge is an ideal attribute of becoming an effective teacher, but the argument seems to be evident that this must be accompanied with pedagogical knowledge (which combine to achieve the feted ‘subject expertise’ (Ofsted, 2008) for it to be worthwhile for a teacher’s practice and children’s learning experiences., so that they can tailor their teaching to suit the inevitable spectrum of pupils’ learning styles and myriad of abilities and personalities which are encompassed within a classroom. Another possible requirement for effective teaching is for a practitioner to be reflective in nature, retrospectively considering incidents (which could be behaviour management challenges or other such entities), so that they can be prepared for similar events in the future and amend their practice as they see appropriate (critical self-appraisal is key to success in this dimension of what constitutes an effective teacher).

All of the attributes mentioned here in this conclusion (and at previous junctures of the assignment) all contribute towards my understanding of what an effective teacher is and will inform my future practice. However, the ultimate defining attribute in what constitutes an effective teacher is probably having the capacity to be flexible and tailor their practice to suit each class that they do teach, whilst maintaining a cohesive ‘teacher identity’ throughout, which allows them to teach pupils competently, ensuring they optimise their learning experiences and are also be schooled in the ‘informal’ curriculum (lessons and life skills which are an adjunct to the academic content which is being taught). Another recurrent theme in this assignment is the importance of pedagogy, with a teacher needing knowledge of the science of teaching to deploy the knowledge (theoretical and experiential) which they have ascertained throughout their career and training.

Essentially, the attributes of sound pedagogical knowledge and flexibility, along with exuding a creative approach in my teaching, are the dimensions which I believe to constitute being an effective teacher. These are attributes which comprise of my own teaching philosophy and are qualities which I will aim to exude in my future practice. However, it is worthwhile noting that this conclusion is tentative (although it is made after a full and rigorous discussion) and needs to be validated by further discussion, evidence and testing.

Ultimately, what makes an effective teacher may be different for each individual (subjective to an extent), although it could be argued that there will be a commonality in people’s opinions of the attributes which make an effective teacher of being flexible, being able to interact well with pupils and possessing sound subject and pedagogical knowledge.

References

Bandura, A. (1977) Social learning theory. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall.

Coe, R., Aloisi, C., Higgins, S. and Elliot- Major, L. (2014) Review of the Underpinning Research. Durham University and Sutton Trust.

Cogill, J. (2008) Primary teachers’ interactive whiteboard practice across one year: changes in pedagogy and influencing factors. EdD thesis, King’s College: University of London.

Department for Education (2004) Every Child Matters. London: DfE.

Department for Education and Skills (2005) Excellence and Enjoyment: Social and Emotional Aspects of Learning. London: DfES.

Department for Education (2010) The Importance of Teaching: The Schools’ White Paper. London: DfE.

Department for Education (2012) Changes to QTS Skills Tests. London: DfE.

Department for Education (2013) GCSE Reform Equality Analysis. [Online]. Available at: https://www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/

277893/gcse_reform_from_2015_equality_analysis.pdf (Accessed: 27 April 2015).

Department for Education (2014) Guidance: GCSE Mathematics. [Online]. Available at: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/gcse-mathematics-subject-content-and-assessment-objectives (Accessed: 01 May 2015).

Department for Education (2015) GCSE Computer Science. [Online]. Available at: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/gcse-computer-science (Accessed: 27 April 2015).

Gardner, H. (2004) Changing Minds: The art and science of changing our own and other people’s minds. New York: Harvard Business School Press.

Gazzaniga, M. (2005) Forty- Five Years of Split Brain Research and Still Going Strong. [Online]. Available at: people.psych.ucsb.edu/…/Forty-five%20years%20of%20split-brain%20r (Accessed: 01 May 2015).

Great Britain. Ofsted (2008) Mathematics: Understanding the Score. London: Ofsted.

Great Britain. Ofsted (2012) Mathematics: understanding the score. London: Ofsted.

Lave, J. and Wenger, E. (1991) Situated Learning. Legitimate peripheral participation. Cambridge: University of Cambridge Press.

Mosston, M. and Ashworth, S. (2008) Teaching physical education. [Online]. Available at: www.spectrumofteachingstyles.org/ebook (Accessed: 01 May 2015).

NCTM (2013) Teaching and Learning Creatively. [Online]. Available at: http://csearch.nctm.org/csearch.aspx?c=all&q=creative%20learning (Accessed: 27th April 2015).

Patel, N. (2003) A Holistic Approach to Learning and Teaching Interaction: Factors in the development of Critical Learners. Brunel Business School.

Pollard, A. (2008) Reflective teaching: evidence-informed professional practice. London: Continuum.

Prensky, M. (2001) ‘Digital Natives, Digital Immigrants’, On the Horizon, 9 (5), MCB University Press.

Qualifications and Development Authority (2011) Personal, Learning and Thinking Skills Framework. London: QCDA.

Riggio, E. R. (2010) Are Teachers Really Leaders in Disguise? [Online]. Available at: https://www.psychologytoday.com/blog/cutting-edge-leadership/201006/are-teachers-really-leaders-in-disguise (Accessed: 27 April 2015).

Ritzer, G. (2007) Blackwell Encyclopaedia of Sociology. London: Blackwell.

Rubio, C. M. (2009) Effective Teachers: Professional and Personal Skills. [Online]. Available at: dialnet.unirioja.es/descarga/articulo/3282843.pdf (Accessed: 27 April 2015).

Rudge, L. (2008) Holistic Education: An Analysis of its Pedagogical Application. PhD Dissertation: The Ohio State University.

Savage, J. (2010) Cross Curricular Learning and Teaching in the Secondary School. Abingdon, Oxon: Routledge.

Schön, D. (1983) The Reflective Practitioner. How professionals think in action. London: Temple Smith.

Shuayb, M. and O’Donnell, S. (2008) Aims and Values in Primary Education: England and Other Countries. National Foundation for Educational Research (NFER).

Shulman, L. S. (1986) ‘Those who understand: Knowledge growth in teaching.’ Educational Researcher, 15(2): 4- 31.

Weick, K. E. (1988) ‘Enacted sensemaking in crisis situations.’ Journal of Management Studies, 24(4).