Essay on the Impact of Bank Flows on House Prices in the UK

Number of words: 2962

Introduction

In the years leading up to the financial downturn, prices of homes quadrupled. To a lot of people, the explanation was that the number of houses was not sufficient. This addresses a portion of the bigger problem. Leading drivers of price increment are banks that can come up with new money each time they lend. During the financial crisis, the banks more than tripled their earnings through mortgage loans. This was the beginning of the problems of high housing prices. Homes can be classified as assets. The prices of houses are not determined by the universal laws of supply and demand that other consumer goods ascribe. Instead, they are greatly influenced by economics. The perpetuated and peddled back story of the chronic housing problems in the United Kingdom is that housing does not cheaply, and it is a privilege of a few. As Farlow (2009, p. 34) asserts, this narrative serves to misguide and mislead the masses while enriching property developers and letting landlords and bankers walk scot-free. Bank of England governor was once quoted remarking that the bank cannot directly solve the underlying problems of the housing crisis.

Studies conducted on the housing crisis

Taltavull and white (2012, p. 354) conducted a study into England’s Central Bank and found out that the bank had a hand at the sky-rocketing prices of housing. By comparing housing prices in the last two decades, they came up with a twenty-year model. This model revealed that the housing shortage had no contribution to the radical rise in prices. Additionally, the study corroborated earlier findings that steep prices of houses are as a result of finance. Notably, they discovered the role played by the Bank of England’s comparatively low-interest percentage, which serves to increase prices of houses. As explained by Taltavull and white (2012, p. 354), the worth of income flows acquired from an asset increases proportionally with lower interest rates. Therefore, this influences the number of persons who are capable of paying to own the asset, the lending amount by banks, and the propensity of borrowers to borrow some more. This, in turn, gives incentives to banks to attract more borrowers and the borrowers to take on more debt. Taltavull and white (2012, p. 362) remark that reduced interest rates are responsible for virtually all real rises in prices for a house since 2000.

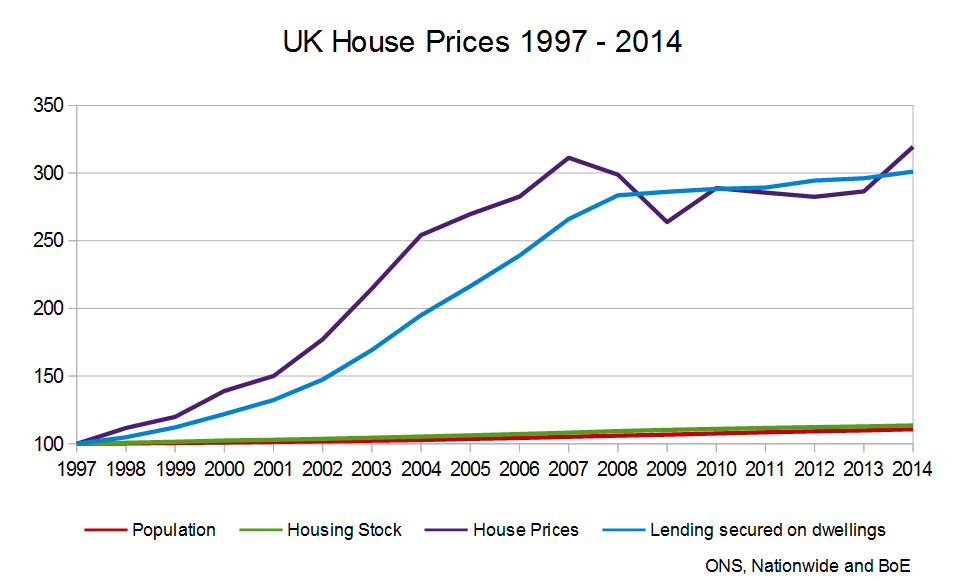

Figure 1: Showing the evolution of housing prices from 1997-2014

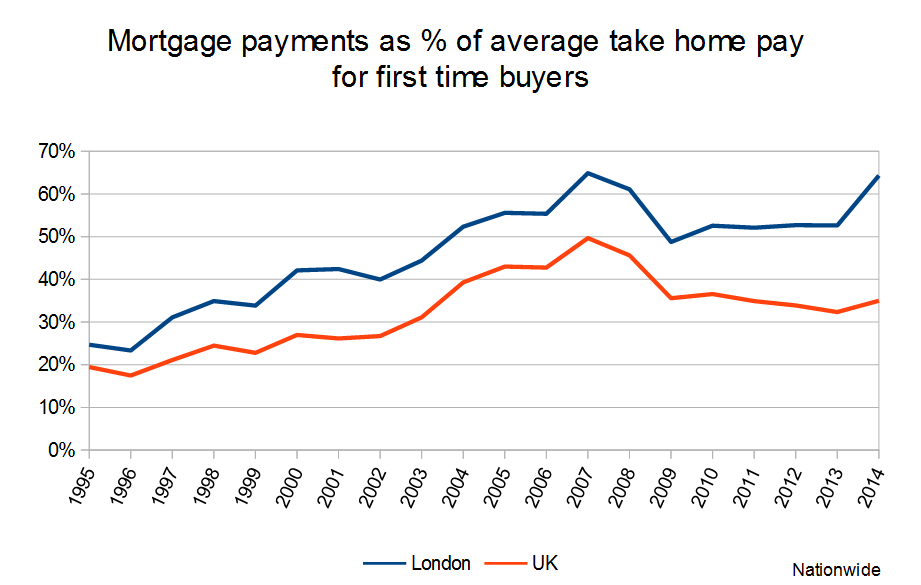

The impact of mortgage repayment on average annual wages

To put everything into perspective, Iacoviello (2005, p. 750) painted the picture of the evolution of the housing price hike. The housing prices influxes are tellingly conspicuous. For instance, in the 1930s, a conventional house with three bedrooms was only one and a half times the average salary yearly. Fast forward to 1997, and the rise in prices of dwellings jumps to a whopping three and a half times the average annual wage. A shocking eight times the average salary annually is the average price of homes in the last twenty years. Consider the capital of England, London, where the cheapest houses are a massive thirteen times the average annual salary of maiden house buyers.

White (2015, p. 12) reiterated the findings of Iacoviello (2005, p. 750). As the wages stagnate, the house prices increase exponentially, making house ownership less feasible. Those who took out mortgages in the advent of the new era of banks, have their salaries “eaten into” for a place to call home. Next, up, rental houses hike rents for tenants. House price increments led to a rapid and substantial rise in the money used in repaying mortgage by first-time owners. For instance, in 1996, 17.5% of the salary of the first-time buyer was used in mortgage repayment. In contrast, in 2008, 49.3% of wages were used. In particular, London’s percentage of salary use on mortgage repayment was 22.2% in 1997, while in 2008, it was a shocking 66.6% (Figure 2).

Figure 2: Showing percentage of average salaries used to repay mortgages

Gaps exposed in early research

The difference in Taltavull and white (2012, p. 354) research is that they did not clearly show and identify the role played by banks in increasing demand for houses. Burgess et al. (2016, p. 34) explain that banks do not loan out reserved savings. Instead, they come up with new money when they lend loans. This means they are not limited in the amount that they can give out credit on account of depositors’ current savings. The capability to make new money by banks hikes the cost of beneficial properties. More than half of the created new money in Britain is allocated to a lending mortgage. Little wonder that prices of houses have sporadically risen and stuck out like a sore thumb in the economy. A closer look at the data shows the major trends in housing prices in the last decade. Stocks of houses have relentlessly risen disproportionately to rise in population. Following the textbook laws of demand and supply, prices of dwellings should be decreasing if they were common goods. Unfortunately, they are not.

A more in-depth look at the political economy of the housing issue reveals that housing supply is one of the drivers amongst many that will require being corrected if the UK will fix the housing issue. Across Britain, there is widespread inequality in housing, and the pressure to access housing is intensely felt. London, for example, has its chronic housing problems. The city is a commercial hub and is involved in wealth movement globally. Badarinza and Ramadorai (2018, p.544) paint an international market where prices have been increased without real earnings being realized. Traditionally, interest rates that are low and movement of investment capital globally take place opportunity hotspots. New Zealand, China, Canada, and Sweden are among countries that are regarded as safe havens for investments. Currently, these countries are grappling with a housing crisis. This is linked to disruptions by the economy on a broader scope and the banking sector. Low-interest rates and a scramble for capital to invest in fixed assets, both residential and commercial property, precedes these disruptions.

Housing crises

Housing issues that occur periodically are a constant thorn in the flesh for industrial economies that started out late. Housing is prioritized as a profit-making venture. Therefore viewed it is viewed as a commodity when in use and commercialized in its consumption. Context is the basis of most crises at national and local levels; however, they are all built on a standard foundation. Productive activities in the economy are ignored for capital accumulation in housing, with housing being a common place for both domestic and foreign investors. Supply systems may find it challenging to deal with policy and land restrictions, but commercialization of housing and radical investment demand increase accounts for the greater struggle (Farlow 2009, p. 34).

Supply systems are encouraged not only to fulfill and solve the housing menace but also to cater to a broader demand. Scarcity occasioned by the failure to satisfy demand fuels the narrative that housing is collateral of the highest quality. Nevertheless, it is not the primary source of commercialization. Presently, the happenings in the UK are fueled by factors that are way beyond the confines of its borders. This voids local mitigation measures due in part to pressures in investment, which are overwhelming or dependent economics on the consumption of housing (White 2015, p. 12).

To express the housing need, projections of households are insufficient. The predictions indicate housing demands and the yearly trends, but their attempt to report household demands is deficient. The scale of need is found in data trends as the lack of housing supersedes the formation of households (Taipalus, 2006, p. 49). In the same breadth, demand restrictions are thought to be a function of the creation of homes, although varied sources drive demand. Taipalus (2006, p 50) notes that economic and population demographic statistics must be utilized holistically to make useful projections of the housing need. The more significant demand composite suggests a steeper challenge in supply if the only response to housing problems is to build more homes.

Supply of housing

It is widely known that to build a home in the UK is a painfully slow and often lethargic process (Hall, 2014, p. 61). The demand for housing does not influence supply, like in other regions of the world (Gurran et al., 2016, p. 68). Nonetheless, the statements mentioned earlier do not in any way mean that the influx in the supply of homes, both rental and bought, will make housing affordable and thus accessible on a broader scale. To ease the problem of demand, the UK government can go the more natural route of overhauling policies of planning and provide incentives to developers. This will provide sufficient housing for all. Unfortunately, this follows the steps taken by the United States government that triggered the global financial downturn (Frydman and Goldberg, 2011, p. 25). The US government failed to consider wealth distribution and over-investment in properties of a residential nature. The 2008 financial downturn had its roots in banking and credit liberalization. The over-concentration on the supply side meant financial freedom to systems of planning and policies of land. A lot of power is placed in the hands of property owners, and this translates to uncontrolled housing prices.

Currently, perspectives on supply are hell-bent on serving the housing demand from the observable resident demographics. There has been a tax relief generously offered to property investors who buy to let. Deregulation on land use that proponents of supply need is not at the on equal standing as pressures of demand that is generated in other areas by deregulation. Environmental degradation is a risk that proponents of extension of housings demand have to contend. Research funded by the government of the UK showed that equity loans granted to first-time buyers spurred the supply of homes. The Central Bank of England is the opinion that the loans do not portend danger of risky behavior (Tse et al., 2014, p 518s). However, the IMF indicated pressures of inflation would be generated by focusing on the demand side more.

Commercialization of the housing crisis

Housing is commonly regarded as collateral of the highest quality, and its performance demonstrates this on a long-term basis as an investment asset. Its performance is optimum in a politically stable environment and in conditions in which planning needs to balance development demand with a myriad of social and environmental considerations. In this respect, planning plays a crucial role in limiting the supply of built properties. However, the commercialization of built assets has catalysts that are different from the controller of the amount generated by planning systems. Marketing has its roots in the economics of houses, liberalization of credit, creation of money, and freedom of banks.

Housing commercialization has causes that are common between countries. With that being said, there are site-specific causes that not only encourage the process but also make the process exhibit attributes of a local nature. For example, in the UK, owning homes has significantly been proposed for the years and years. House renting has been discouraged and viewed inferior as well as unsustainable for a family setting. Renting does not also offer or facilitate the transfer of wealth between generations. In the UK, housing is treated as a vehicle for the creation of wealth by using an owned property to acquire loans for property proliferation. With a home, one can create wealth, transfer wealth, or use the feature as a fall back plan in retirement.

Credit plans previously defined prices of houses in Britain based on the way the house is built and also how it is sold. Houses are made for a pre-determined clientele, and before completion, housing prices are determined to demand expectations. Therefore, the need to supply the market when conditions of demand are favorable is the underlying logic, thus, increasing profits regardless of construction volumes (Buckley and Ermisch, 1982, p. 304).

In the commercialization of housing, credit flow is, to no small extent, impactful on prices of houses (de La Paz and White, 2016, p. 35). After the 2008 financial crisis that rocked the globe, more focus was directed towards the channels by which prices are affected by credit. The attention was also on how easily loans were accessible and how this led to over-investment trends. The over-investment then inflated personal loans to unsustainable levels, and banks could not recover money from “bad” loans through foreclosures and subsequent sale. The commercialization of housing was so prevalent that the worth of houses did not correlate with the debt amount associated with it. Banks have been in the driving seat in the commercialization of dwellings. Lending decisions have separated property values from their earnings. The lack of control in bank loans has resulted in money being “created” to equal house value proposals (Hall, 2014, p. 61). Banks uncontrollably supply the economy with money, and this is not matched by the supply of housing, causing commercialization and risks of systemic proportions. Built houses not demanded serve as storage of newly acquired money or foreign exchange earnings.

The biggest motivation of any business is to make profits. Banks are no different. Economically-stable periods present banks with the opportune time to lend such that “created” money increases. Accordingly, house prices soar, and also instability is occasioned by over-investment. Badarinza and Ramadorai (2018, p.544) have demonstrated by the use of historical and current data from UK’s economy between 1900 and 2009, that growth of credit creates the optimum predictive tool of unstable finances.

To make huge profits, banks direct the economy to the dependency on built assets and away from other vital sectors such as manufacturing. To generate or “create money,” the bank prefers to lend loans to collaterals of high-quality e.g., homeowners. In the event business owing money to the bank fails, the bank will be the sole loser. On the other hand, if a propertied person were to default on repaying a loan, the bank would retrieve its money from the sale of the property. The property is sold in a market situation where the liberal credit process controls the prices that the bank is a part of. Needless to point out, the bank profits substantially from defaulters.

Conclusion

At the epicenter of the current housing, the problem is that the housing supply is limited in ways that demand investment is not. Moreover, the unregulated banking sector supplies infinite amounts of money to the economy. This leads to mortgage loans that supersede the supply of new houses. The housing crisis solution is to reduce prices and manage demand considerably gradually. Policy frameworks that continually provide a conducive environment for the few property owners should be discarded. Policymakers should reinstate credit control measures, limit the number of lenders associated with mortgages, and maintain and uphold the functions of building societies. The central Bank of England, for example, has made significant contributions to the housing crisis in the country. This is by persistently dropping interest rates that increase prices of assets, thus making property ownership a mirage for many. The extremely priced houses serve to pass on wealth between different generations, between social classes and between homeowners and those who do not have homes.

Some asset owners do not profit from increased house values. Those selling their houses will discover that the same margin has elevated other home prices. This means there is no advantage. Reality check, however, reveals that banks and those asset-wealthy individuals are the primary beneficiaries. When the prices of homeowners are hiked, it means that prospective homeowners will have to borrow more for an extended period. This is overall, translates to increased monies for the banks in payments for interest rates.

References

Badarinza, C., and Ramadorai, T., 2018. Home away from home? Foreign demand and London house prices. Journal of Financial Economics, 130(3), pp.532-555.

Buckley, R., and Ermisch, J., 1982. Government policy and house prices in the United Kingdom: an econometric analysis. Oxford Bulletin of Economics and Statistics, 44(4), pp.273-304.

Burgess, S., Burrows, O., Godin, A., Kinsella, S., and Millard, S., 2016. A dynamic model of financial balances for the United Kingdom.

De La Paz, P.T., and White, M., 2016. The sources of house price change: identifying liquidity shocks to the housing market. Journal of European Real Estate Research.

Farlow, A., 2005. UK house prices, consumption, and GDP in a global context. The memo, Department of Economics and Oriel College, University of Oxford.

Frydman, R., and Goldberg, M.D., 2011. Beyond mechanical markets: Asset price swings, risk, and the role of the state. Princeton University Press.

Gurran, N., Gallent, N. and Chiu, R.L., 2016. Politics, planning and housing supply in Australia, England and Hong Kong. Routledge.

Hall, P., 2014. WHY ARE THE GREAT ‘STUCK SITES’STUCK?. Centre for London 2014© Centre for London. Some rights reserved. The Exchange 28 London Bridge Street, p.61.

Iacoviello, M., 2005. House prices, borrowing constraints, and monetary policy in the business cycle. American economic review, 95(3), pp.739-764.

Taipalus, K., 2006. A global house price bubble? Evaluation based on a new rent-price approach. Evaluation Based on a New Rent-Price Approach.

Taltavull de La Paz, P. and White, M., 2012. Fundamental drivers of house price change: the role of money, mortgages, and migration in Spain and the United Kingdom. Journal of Property Research, 29(4), pp.341-367.

Tse, C.B., Rodgers, T. and Niklewski, J., 2014. The 2007 financial crisis and the UK residential housing market: Did the relationship between interest rates and house prices change?. Economic Modelling, 37, pp.518-530.

White, M., 2015. Cyclical and structural change in the UK housing market. Journal of European Real Estate Research.