Essay on Is a Materialistic Value Orientation Detrimental to Well-Being?

Number of words: 2663

Introduction

Prior to entering the academic nature of this assignment, it seems pertinent to define the question in real life, simple terms before progressing to a more theoretical take on matters. There has long been a debate over whether money can make an individual satisfied and fulfilled in life, with some arguing that it is the key to happiness, whilst others may deride it as something which is immaterial, with family, love and relationships a more important priority. In academic terms, someone who values money, possessions and other such frivolities over interpersonal elements in purchasing a product is deemed to have a materialistic value orientation or being a believer in/proponent of materialism (Kasser et al., 2013). In other words, someone who is of this disposition may purchase certain goods and other such merchandise (or determine their levels of self-worth by the amount of money that they have/earn) in the hope that it will instil a ‘feel good’ factor in them and lead to enhanced feelings of self-worth and happiness, which could possibly be to compensate for low self-esteem (this sentiment is explored in a later section of this paper in more depth) (Dittmar et al., 2014: 880). It has been widely disseminated in the literature as to whether a materialistic value orientation does lead to increased well-being, or whether it in fact has a detrimental (converse to the original intention of purchasing such goods) impact on the individual’s well-being. This is something that this paper will attempt to critically discern (through looking at the issue in terms of a career, consumer and personal dimension of a materialistic value orientation) prior to coming to a tentative conclusion (the limited wordage of this assignment and the fact that further research is needed to evidence this render the conclusion to not be completely definitive). Various psychological theories will also be intertwined with this assignment to provide a theoretical premise to the assignment and allow for literature, theory and other information to be cross-referenced and triangulated.

What is well-being?

The precise constitution of the term ‘well-being’ needs to be identified, before progressing to the main body of the assignment which assesses the impact of a materialistic value orientation on well-being. Nevertheless, some examination of the assignment question will be made in this section.

WHO (2014) define well-being as being something which is equitable to good mental health, where an individual can contribute to their community in their career, personal life and be able to function effectively. Here, in this definition well-being seems to refer to an absence of mental health disorders and ailments and relative psychological health of the individual. In relation to the context of the assignment, someone who has a materialistic value orientation may not be mentally ill or have any problems with their mental state. However, if it were to become a fixation to earn a significant amount of money or possess an innumerable amount of possessions, then this could be conjectured to have a detrimental impact on their level of well-being, particularly if it were to cause them unnecessary stress and discontent which could have been avoided if they did not have a materialistic value orientation.

However, this definition of well-being above is slightly limited in that it only focuses on one aspect of the health of an individual (their mental health) and is quite negative in its nature, assuming that an absence of problems equates to well-being rather than satisfying desires as being indicative of the well-being of an individual. Arguably, someone who has a materialistic value orientation does satisfy their own desires in terms of purchasing behaviour and levels of financial wealth, which seemingly implies that being of such a disposition can impact favourably on well-being, rather than having a detrimental impact.

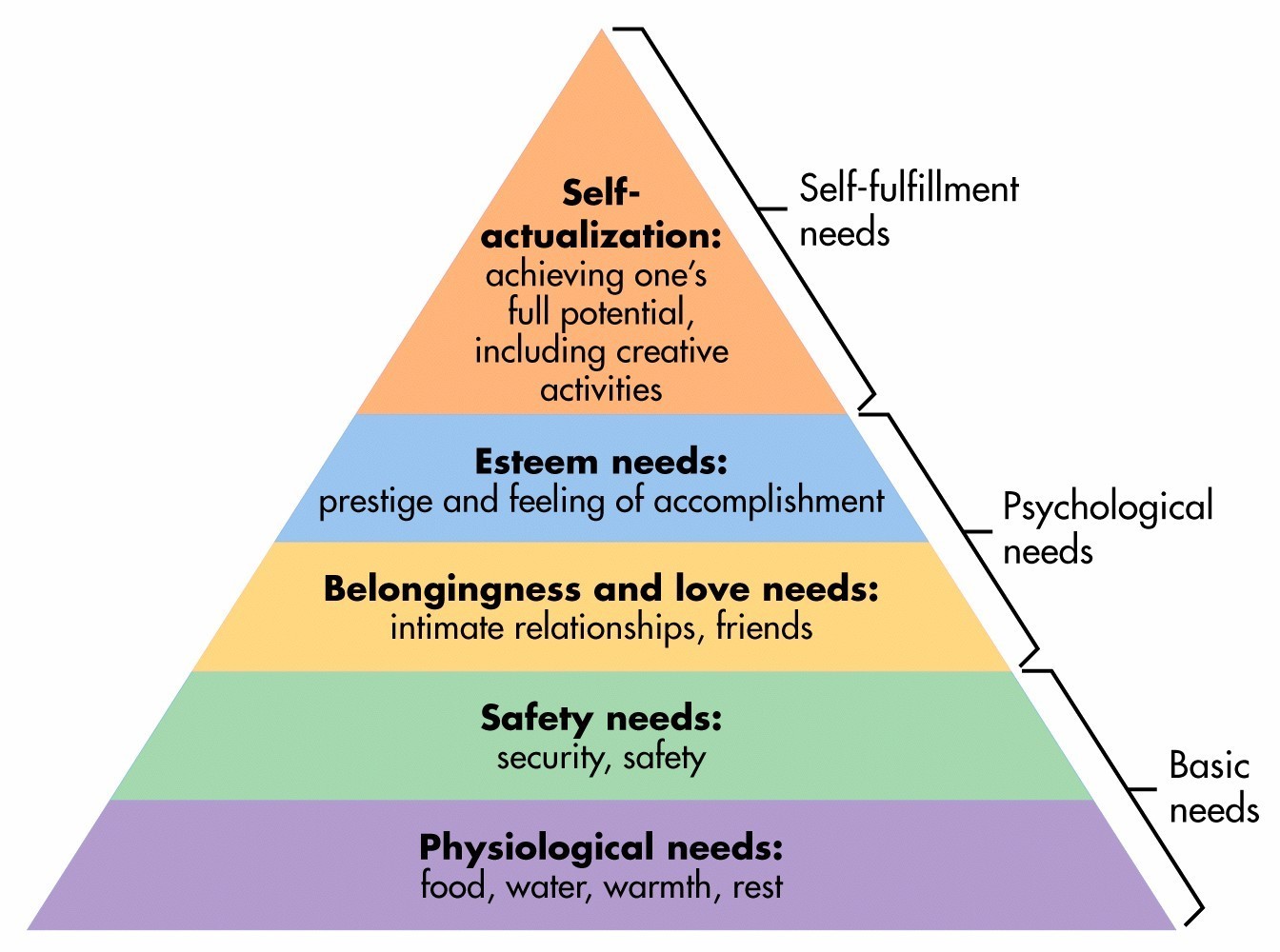

A different conceptualisation of well-being (which does focus on psychological needs being met) is perhaps the most authoritative measure of representing the needs of the human psyche, Maslow’s (1970) Hierarchy of Needs. This lists the basic needs which an individual needs to fulfil and satisfy in order for them to achieve a certain level of well-being. Arranged in a pyramidal structure, the model purports that basic ‘deficiency’ needs (shelter, food etc.) need to be met before the individual can access the higher levels of the model (which presumably lead to enhanced and accentuated well-being) such as self-esteem and the ultimate feted accomplishment of self-actualisation (where one fulfils their ultimate potential):

Figure 1- Maslow’s (1970) Hierarchy of Needs

Upon even a cursory glance at the model, it is evident that some level of financial resources is needed to access some of the different dimensions of the pyramid (such as having the level of income to provide shelter and sustenance for themselves and their families). This seems to infer that a materialistic value orientation could actually have positive implications on one’s well-being if it allows them to progress to the uppermost levels of the hierarchy, although Maslow (1943) expounds that characteristics of those that are self-actualised tended to be those who (alluding to the career aspect of materialistic value orientation) who were motivated to pursue their work for feelings of fulfilment and not financial remuneration (as it could be assumed that an individual with a materialistic value orientation would do). The inference from this could be made that those of a materialistic value orientation may not be able to reach the prized level of self-actualisation, thus consequently diminishing the level of well-being which they can have access to. Nevertheless, Maslow (1968) does concede that what constitutes self-actualisation (and well-being) for each person is different, a statement which is ratified by Tay and Diener (2011) who note that well-being is an extremely subjective entity and that perception of well-being will vary from person to person. Some may find it in academic achievement, others through relationships and well-being, whilst a selection of individuals may achieve such personal fulfilment through reaching a certain level of financial wealth. The latter mentioned requisite of well-being infers that those who are of a materialistic value orientation (and presumably place great importance on the amount of money that they earn) can achieve some level of well-being, but only if they have the emotional intelligence and capacity to be able to feel that they have been fulfilled (Goleman, 1996).

Now that the psychological tenets of well-being have been appraised (and their relevance towards one who has a materialistic value orientation has been communicated), the assignment will now progress to a more informed look at the issue with empirical literature surrounding the concept being addressed and espoused in the literature.

Materialistic Value Orientation and impacts on well-being

Early indications of the impacts of a materialistic value orientation on well-being have been mixed: with some theories arguing that it is subjective and dependent on the individual (Maslow, 1970 etc.), whereas others (Dittmar et al., 2014) are more definitive in the detrimental impacts of the orientation towards one’s well-being.

Beginning rationally in a chronological order in disseminating the concept, in an early paper on the concept, Belk (1984) outlines three dimensions of a materialistic value orientation: possessiveness, non-generosity and envy. Even without exploring the later content of the paper that he ascribed, this already infers the negative aspects of a materialistic value orientated person, that they will exhibit some of the characteristics of the aforementioned traits. Indeed, Belk progressed in his paper to come to the conclusion that a materialistic value orientation was associated with a lower level of well-being in individuals who were motivated in such a way. However, further explanation on why this is the case needs to be provided. Kasser (2002) reiterated Belk’s point that materialism can be equated with a lower sense of well-being in individuals who have such an orientation rather than those that do not, citing the work of worldwide studies which have come to this conclusion. In reference to the previous section, Kasser (2002) also interpreted the works of existential thinkers such as Maslow (explained earlier on) in rationalising that people’s levels of well-being is not influenced by their levels of wealth and collection of professions, instead that being more dependent on the interactions/relationships they hold with individuals and the quality of experiences that they have in their lives. Deliberating the precise impacts which a materialistic value orientation can have on individuals, Kasser (2002) theorised that people adopt such values to cope with personal insecurities which they may be facing or feel lurking in them, with a materialistic value orientation being a coping mechanism for them to deal with such crippling tremors of self-doubt. Furthermore, he rationalises that if this materialistic value orientation takes importance ahead of other such dimensions of their life (i.e. personal relationships, fulfilment and hobbies/outside interests), then this can lead the individuals to feel bereft and depressed, as they feel a gaping hole or chasm in their life which cannot be filled sated with purely financial resources. The title of Kasser’s book: The High Price of materialism, eloquently sums up his arguments.

Kasser is not the only author/scholar to be highly critical of materialism: Chaplin and John (2007) note the impacts that materialism can have on self-esteem, particularly on children and adolescents who have a fragile self-esteem (although this argument could be perceived to be highly generalised and not recognising the individual differences amongst children). Specifically, Chaplin and John (2007) note that the peer pressure on children to purchase certain brands and be materialistic to a certain extent (particularly in westernised nations, where it is supposed that brands are viewed as a sign of status and prestige), can make them feel depressed, morose and a shadow of their true selves. This seems to imply that the movement (or obsession/indoctrination depending on one’s viewpoint of the matter) to be materialistic may actually be the main cause of unhappiness in materialistic individuals, rather than actually having a materialistic value orientation themselves. Simply, it may be the cause and not the symptom which may cause such unrest and despondency in materialistic value orientated individuals. Further credence to this strand of reasoning is provided by Srivastava et al. (2001). In their research they do concede that a body of previous research has identified that the relative importance that a person attaches to money tends to have a negative correlation with their happiness i.e. the more value they attach to money, the less happiness and contentment that they experience. However, the authors delve further into what precisely makes materialistic individuals experience an inferior level of well-being to their non-materialistic counterparts. This entailed them scrutinising exactly what motivated people (specifically a sample of business students) to make money, finding a commonality of seeking power, endorsing themselves to others (‘showing off’), attaining power or prestige, or finally by compensating for a lack of self-esteem and doubt (a point which was referenced earlier in this assignment). Again, this seems to be irrefutable evidence that the negative impacts of materialism cannot only be attributed to actually possessing a materialistic value orientation, it is also due to the underlying reasons as to why a person may have such an orientation.

This could be potentially explained by Ryan and Deci’s (2000) self-determination theory and the concept of motivation, with other theories rationalising this. Ryan and Deci (2000) postulate that materialistic value orientated individuals may have minimal reserves of self-determination (which is the ability of the individual to self-motivate themselves to perform tasks without any external influences and interferences) as they are predominantly motivated by money and obtaining material possessions, rather than performing a task or action for the enjoyment and satisfaction that they can derive from completing it. This leads into a discussion of how materialistic value orientation affects the domains of one’s life specifically. Arguably, Ryan and Deci’s theory could be potentially applied to the workplace and explain the dissatisfaction that materialistic value orientated individuals experience. Work is undoubtedly a significant influence on one’s happiness, given the amount of time that they spend in the workplace. The supposition could be made that an individual who is materialistically value orientated may only be extrinsically motivated by financial rewards or the chance to achieve acclaim and a plethora of material possessions, which may lead them to be less satisfied and experience lower levels of well-being than one who is intrinsically motivated to perform the work due to their enjoyment of the task or the self-worth which they gain from it (Coon and Mitterer, 2010). Adding further weight to this argument, Allen and Meyer (1991) put forward a three-dimensional model of commitment: affective (where an employee has an emotional attachment to an organisation), continuance (where a worker feels almost trapped in their role and cannot leave because of the financial and social rewards of the position) and normative (where the employee feels obligated to stay with the organisation, possibly out of a sense of loyalty if they have enjoyed a lengthy tenure there or because of the resources that their employer has invested within them such as training). Combining the psychological and business perspectives of this matter seems to infer that those who have a materialistic value orientation may have continuance commitment and thus will experience less satisfaction in their role and ultimately, their life.

Conclusion

This assignment has arrived at the conclusion that having a materialistic value orientation is detrimental to well-being, but it may be the motivations that drive that individual to possess such an orientation may have the most damaging effect on one’s well-being.

As a suitable denouement to this assignment, it seems apt to close this textual piece with a poignant quote/proverb relating to the pursuit of happiness and well-being:

‘If you want to feel rich, count the things you have that money can’t buy.’

References

Belk, R. W. (1984). Materialism: Trait aspects of living in the material world. Journal of Consumer Research, 12, 265-280.

Chaplin L. N. and John, D. R. (2007) Growing up in Material World: Age differences in materialism in children and adolescents. Journal of Consumer Research. 2007; 34(4):480-493.

Coon, D. & Mitterer, J. O. (2010). Introduction to psychology: Gateways to mind and behavior with concept maps. Belmont, CA: Wadsworth.

Ryan, R. M., & Deci, E. L. (2000). Self-determination theory and the facilitation of intrinsic motivation, social development, and well-being. American Psychologist, 55, 68-78.

Dittmar, H., Bond, R., Hurst, M., & Kasser, T. (2014). The relationship between materialism and personal well-being: A meta-analysis. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 107, 879-924.

Kasser, T. (2002). The high price of materialism. Cambridge, MA: MIT.

Kasser et al. (2013). Changes in materialism, changes in well-being: Three longitudinal and one intervention study. Emotion and Motivation.

Goleman, D. (1996) Emotional Intelligence: Why it matters more than IQ. New York: Bloomsbury Publishers.

Maslow, A. H. (1943). A Theory of Human Motivation. Psychological Review, 50(4), 370-96.

Maslow, A. H. (1968). Toward a Psychology of Being. New York: D. Van Nostrand Company.

Maslow, A. H. (1970). Motivation and personality. New York: Harper & Row.

Meyer, J. P.; Allen, N. J. (1991). A three-component conceptualization of organizational commitment. Human Resource Management Review. 1: 61

Srivastava, A., Locke, E. A. & Bartol, K. M. (2001). Money and subjective well-being: It’s not the money, it’s the motives. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 80, 959-971.

Tay, L., & Diener, E. (2011). Needs and subjective well-being around the world.Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 101(2), 354.

World Health Organisation (August 2014) Mental Health: A State of Well-being. Retrieved from: http://www.who.int/features/factfiles/mental_health/en/