Dissertation On to What Extent and How Were Women a Political Force in Weimar Germany

Number of words: 13197

Introduction

“All Germans are equal in front of the law. In principle, men and women have the same rights and obligations.”[1]

November 1918 saw dramatic change to the political landscape of Germany. The abdication of the Kaiser and proclamation of a republic were momentous upheavals followed by a constitution allowing all adult Germans the right to vote. For the first time in the history of the German states the electorate included women. Far from being a minority group that would have a largely insignificant impact on electoral results, women had abruptly become the largest demographic with the right to cast a ballot.

It would be logical to assume that such an important event would have been subjected to considerable and detailed study; however until relatively recently historiography has contained few serious attempts to examine the role of women in the political world of Weimar Germany. For a great part of the twentieth century women were considered to base their political opinions entirely on emotion. This idea is intrinsically Freudian and was upheld by men such as Joachim Fest, Hermann Rauschning and Richard Grunberger.[2] Fest devotes pages to his out-dated and bizarre psychoanalysis, in which he attributes the success of Hitler’s political speeches to the “…excessive emotionalism…”[3] and “…motherly…”[4] feelings of women towards Hitler and refers to their behaviour at rallies as like “…the public sexual acts of primitive tribes.”[5] Whilst Grunberger provides useful statistics in regard to women in Weimar Germany, he talks of the “…emotion guided woman” and suggests that the entire female crowd at public occasions would show “…a form of mass hysteria known as Kontaksucht…”[6]

Among more recent academics is Julia Sneeringer who argues that “…the gender dimensions of political mobilization have remained largely invisible in German historiography.”[7] This is a much more plausible statement than the assertion of mass hysteria being women’s only notable characteristic in regard to politics in the Weimar period. It has been academics such as Sneeringer, Cornelie Usborne and Raffael Scheck who have, in recent years, covered much ground in providing a realistic analysis of women in Weimar Germany. Scheck’s work on right-wing women has provided much insight into the aspirations and opinions of this group, orientating the work beyond the question of Hitler’s popularity, which dominates much of the previous historiography. Usborne has discussed important issues, such as the abortion debate and the way in which female activists engaged with them in a political setting.

Whilst this dissertation will be examining the impact of female emancipation in Weimar Germany, it will also consider the rights that women did not yet have, such as the entitlement to abortion. Although women had more legal rights than their counterparts in many other countries, they did not have equality with men in all spheres of life, as would be implicit in a modern Western context. Many people still considered a woman’s ideal place to be in the household; emancipation is a process and could not conceivably have materialised overnight with the Weimar Constitution. This is not to ignore the large changes that were taking place regarding women, such as involvement in political parties. It is exactly in this historical context that the emancipation of women should be considered.

With motherhood at the forefront of many women’s lives, it is essential to consider their political activities in this area. The general decline in birth rates and the devastating impact of WWI and the 1918 influenza pandemic, (which inspired a children’s skipping rhyme “I had a little bird, its name was Enza, I opened a window, and in-flu-enza”[8]) had led to a population crisis in much of Europe. This study will, therefore, consider the laws and politics surrounding issues such as abortion and contraception. In much of the twentieth century literature surrounding Weimar and Nazi Germany, these issues have not been given significant scope, something which feminist historians in the last few decades have sought to remedy. It is of great importance to consider the choice to have or not have a family when analysing women’s emancipation, as without that choice a woman inevitably finds herself without certain freedoms, such as sexual or economic.

The rise of the ‘new woman’ is also of vital consideration in a study such as this. This woman was perceived as considerably different to her predecessors. With independence and an income of her own, she had a potent sexuality and was controversially masculine in her appearance. Whilst many more liberal Germans welcomed such liberation, right-wing men and women saw her as a dangerous figure, threatening the recovery of the population. It was concerns such as these that made the phenomenon of the ‘new woman’ and the refutation of any positive connotations it may have had that make it of great importance to a true understanding of women and their involvement in Weimar politics.

Due to the limited extent of this study German women will be largely considered on a national, rather than a regional, basis. It should not be assumed, however, that there were not considerable differences in the way in which politics and law impacted on women from different class and religious backgrounds. Although all German women were enfranchised in national and local elections, it is important to note that Jewish women were not fully enfranchised in regard to their local community. As a religious entity in Germany the Jewish community was able to tax its members and appointed its own communal leadership. Only Jewish men were allowed to vote in Jewish assembly elections and despite long-term, organised campaigning, Jewish women had not won the right to vote in the assemblies in all seven regions by the end of the 1920s.[9] Many Jewish women put considerable effort into attempting to rectify this issue. However this did not result in their neglect of national politics. Rosa Luxemburg, a Jewish woman of Polish origin, played a significant role in Weimar politics, especially in relation to the KPD and SPD, demonstrating that with determination a woman could be involved in German politics to a great extent. It is in this context that Luxemburg deserves particular consideration in chapter one of this study.

The intention of this work is to examine the extent to which women were a true and important political force in Weimar Germany, despite prejudice and no precedent of direct involvement in the Reichstag. Germany went through intense upheaval during the Weimar period in areas as diverse as culture, economics and moral values. The response of German women to their changing society has left scope for a fascinating historiography, towards which this study will hopefully make some small contribution.

Main Text

Chapter One – Setting the Scene: Pre-Weimar Female Activism and Pre-Weimar Problems in an International Context

Of all the pre-Weimar female activists, Rosa Luxemburg was certainly one of the most talented working in Germany. A Polish exile, as “…Rosalia Lübeck… [she] acquired Prussian citizenship through marriage.”[10] This was a marriage of convenience; the reference in her letter to her lover was not accompanied by any personal information about her new husband. Continuing to work under her maiden name, Luxemburg worked with Karl Liebknecht to found the Spartacus League, printing anti-war propaganda and taking to the streets in protest.[11] At twenty three Luxemburg made her first public speech and at twenty four was editor in chief of The Workers’ Cause published by the Social Democracy of the Kingdom of Poland (SDKP).[12] In addition to this, Luxemburg edited a newspaper for the German Social Democratic Party (SPD) upon their invitation in 1898.[13]

Luxemburg did not confine her work to a single country. She believed in the necessity for international, rather than national action,[14] in her letters to Leo Jogiches whilst she was in Paris, Luxemburg demanded copies of newspapers and information about Germany, Austria and Poland, writing scathingly that the “…French newspapers print nothing but Parisian trivia.”[15]

She believed that women were one of the many groups that would have all the rights they lacked under capitalism once there had been a communist revolution,[16] although she became more concerned with the emancipation of women and the increasing conservatism of the German Social Democratic Party and spoke at an International Women’s Conference in Holland in 1915.[17]

It is clear that Luxemburg was a sophisticated thinker, even in her early twenties, showing that a woman could be active in German politics before the Weimar Constitution gave them greater rights and freedoms on paper. Her written work, speeches and determination to be a player on the international stage, show that women were capable of being involved in politics even whilst banned from government positions. Her work for the German Social Democratic Party proved that an intelligent woman could gain the attention of politicians in an undoubtedly male world. Luxemburg even fought the constraints of imprisonment, her work still appearing in Spartakusbriefe, having been smuggled out of various prisons.[18]

The ability to create change in society, particularly in the political sphere, was especially difficult for Rosa Luxemburg and other female activists in Imperial Germany due to the law in many German states which prevented women from participating in political organisations. This law was not revoked until 1908, although the new law impacted the majority of Germans states. There were, however, some in which it did not take effect until the advent of the Weimar Republic and the Constitution.[19] This prevented the formation of a large and effective suffrage movement across the country, leaving many activists reliant on working within subdivisions of political parties, such as the SPD.

The SPD’s official program from 1890 to 1919 demanded female suffrage and an end to gender discrimination in public and civil law.[20] The women’s suffrage movement within the SPD was notably working class. Its main feminist counterpart was the Federation of German Women’s Associations, although it should be noted that thousands of their members actually opposed female suffrage.[21] Despite the demands within the official programs, there was discrimination against women within the SPD, as well as women on the whole being openly discriminated against in most areas of their lives.[22] The female section of the SPD was forced by law to officially exist as a separate entity to the main party; the resulting independence was a trait which continued after the Weimar Constitution.[23] This shows that, although their activities were restricted by law within Imperial Germany, working class women did operate as a political force of their own volition, creating a framework that continued to function with the greater freedom women found in the Weimar Republic.

It is notable that the main demand of female activists within the SPD in the late nineteenth century was not for emancipation, but for improved conditions and pay for working class women with jobs such as domestic servant and factory worker.[24] This is in part due to the fact that the majority of women working within the SPD were working class women living in poor conditions, the improvement of which they viewed as a much more necessary requirement than obtaining the vote. Despite the major concern of women in the SPD not being to gain the vote, it did form part of their agenda, as well as that of the party at large. They were in fact more progressive than the bourgeois, with women from the Mittlestand beginning to argue for the vote at the later date of 1902.[25] The women’s division of the SPD grew steadily in number in the years preceding WWI, taking on large numbers of housewives and increasing their demands correspondingly.[26] It is clear that, despite the classes not working together politically, or having the same priorities, thousands of women across the social spectrum were determined to use politics to improve their lives.

The way in which women were able to function politically changed dramatically with the revolution of 1918, which saw the enfranchisement of all adult women in Germany. Political parties found themselves needing female votes for the first time, as women suddenly became the largest group with the right to vote in the country.[27] This abrupt change in political demographics was in theory a victory for the left, who had long since believed that women’s emancipation would greatly expand their support base.[28] However this was not to prove the case in the long run. Although thousands of women had been active in trying to improve their lives through political means, there were many who did not support their own emancipation. The vote for women had arrived in Weimar Germany due to the compromises of the Constitution, not as a result of a strong fight on the part of the female population. This is an important consideration in a study of women and politics in Weimar Germany, as there were thousands of women who had previously had their political rights limited by law, who were suddenly able to vote in national elections. They therefore had no previous voting pattern, yet were the most influential demographic at the poles. Their support was important to all the political parties, whether they were for or against female emancipation.

It was not, however, just the political status of women that was undergoing change in this period. At the end of WWI there were 500,000 war widows in Germany.[29] This was an unprecedented change with important social consequences. Thousands of women had become the heads of their households and were unlikely to remarry due to the lack of available men. This meant that the likelihood of them having more, if any, children was drastically reduced at a time when the population was in crisis.

Weimar Germany was not alone in undergoing tremendous demographic change. By the end of World War One populations had been decimated by the conflict and it is possible that, combined with the Russian Revolution and diseases such as the 1918 influenza pandemic, the death count for the period in Europe was around thirteen million.[30] In addition to this there had been a long term decline in birth rates towards the end of the

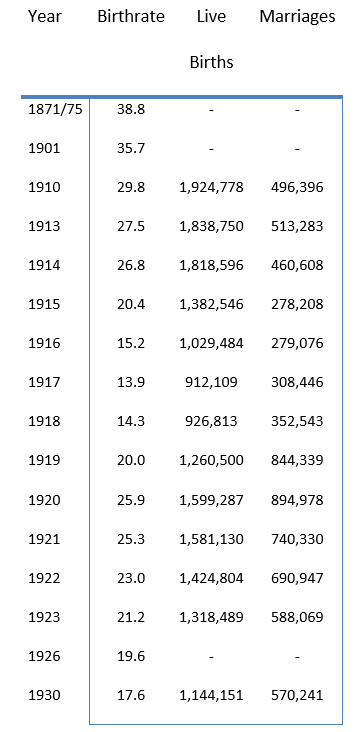

nineteenth century and during the early twentieth century.[31] This pattern continued in Germany until the mid-1930s, with only a few minor and temporary increases in addition to the obvious impact of WWI in 1917 and 1918. (see figure 1)

Figure 1 Crude birthrate, number of live births and number of marriages in Germany[32]

Due to these extreme factors, governments across the continent felt they should intervene in the private lives of their populous, as they feared the loss of power associated with population decline as well as damaged economics and social unrest.[33] Abortion was either discouraged or criminalised in most European countries, whilst healthy living was promoted and attempts to improve housing became a serious political matter.[34]

The population problems within Europe were made worse by the high suicide rate among veterans across Europe.[35] With many doctors not recognising post-traumatic stress disorder as a genuine illness or knowing how to treat it, psychiatric assistance for thousands of veterans was largely unavailable.[36] Many German doctors would either refuse to allow veterans treatment in institutions, considering their symptoms to be a lack of willpower in overcoming their frontline experience,[37] or would make their stay unbearable in the hope that they would leave. It is clear that this would have impacted on thousands of women, as male relatives were unable to function as they would have before WWI, leaving their families with emotional and financial difficulties.

Whilst European governments strove to improve both the numbers and health of their populations, many began to look at the prevention of disease. They were aware that many illnesses could run in families and Germany was not the only country to enforce sterilization of the physically and mentally ill.[38] Such extreme policy demonstrates how important the family, traditionally the domain of women, had become to most European nations, thus increasing the impact of politics on women’s day to day lives.

The perceived need for the state to play an active role in the public’s private lives, and especially in the family, was not a purely right wing concept. The radical French politician Édouard Herriot argued in 1919 that “A nation is not a collection of individuals placed beside one another; it is a group of interlocking families.” [39] This attitude contrasts starkly with the increasing independence of women who had found themselves in new roles during WWI.

By the start of the Weimar Republic there were more women in employment throughout Europe. Having gained a place in the workplace during World War One, such women had greater demands than before for equality, full lives and sexual freedom.[40] This was the opposite to the desires of European governments who wanted to increase their populations and was not regarded as a positive change among much of the traditionally dominant male population. Mark Mazower gives Tuppence Beresford, the heroine of Agatha Christie’s novel The Secret Adversary, as an example of the kind of young woman “…increasingly denounced as manifestations of ‘sexual bolshevism’, threatening the traditional authority of the male.”[41]

The desire to increase population was more dominant in the priorities of many European governments than a consideration of the rights of women. In the USSR, after the revolution, women had been given full legal rights, including the ability to petition for divorce. Despite this immense step forward Joseph Stalin returned the government to the promotion of traditional families. This was due to a vast increase in divorce and abortion rates.[42] Although communist values placed women as the full equal of their male counterparts, Stalin was as concerned as many other heads of state about the decrease in population and was prepared to allow the emancipation of women to take a backseat in order to increase the populous. This shows that even the extreme left wing of politics could not always be counted on by women to support them and highlights the necessity for women to fight for equality themselves.

The USSR, despite a reticence to encourage women to exercise their rights, was still much more progressive than many other European countries when considering the ‘woman question’. Countries such as Greece, France and Italy did not allow women to vote, keeping their discriminatory laws in place for longer than Germany. Although Britain was faster than many other countries to meet the demands of the female population, only a limited number of women were able to vote prior to 1930.[43] It is in this international context that it becomes clear that in 1918 the Weimar Republic, despite not going as far as the USSR, was much more advanced in the issue of women’s rights than many of its European counterparts.

Chapter Two – Weimar female activism and issues: Work and the Hausfrau, contraception, the abortion debate and the ‘new woman’

During WWI thousands of women had moved into the workplace to replace men who had been sent to the front. At the advent of the Weimar Republic there were more women than ever before in employment. However there was also high unemployment with the country’s army being drastically cut by the Treaty of Versailles. Although they had proven themselves confident in the manual work normally carried out by men, women were relegated to white collar work.[44] The presence of women in the workforce was not insignificant however, with approximately one third of German women in employment during the first quarter of the twentieth century.[45] The Weimar Constitution had entitled women to equal pay and other rights including maternity leave; their presence in the workforce and their rights had become a political issue.

Despite their newly enshrined legal rights, women working in white collar sectors earned an average salary that was only two-thirds of their male colleagues.[46] As such, female workers were a desirable commodity for many employers, as they were in many European countries. This resulted in men being made redundant more often than women during the Depression.[47] The resentment felt towards working women during times when thousands of men struggled to find employment can be seen clearly from its manifestation in German language, the derogatory term Doppelverdiener[48]came into common use to describe women who worked whilst their husbands were employed. It is a peculiar irony that women were disliked due to a desirability that stemmed from an abuse of their legal rights.

In 1932, before the NSDAP took power, a law was passed allowing female civil servants to be fired once they were married. It was called the ‘Law Governing the Legal Status of Female Civil Servants and Public Officials’[49] and meant that, for the 20,000 female graduates in Weimar Germany,[50] marriage could be a career destroying prospect. After years of study a woman could find herself totally dependent on her husband’s income, a very clear sign that even though women had the vote, their status was far from equal to that of men. Despite the law being a step away from the full equality wanted for women by political groups such as the KDP, many women themselves did not oppose it. Thousands believed in the idea of work as a temporary phase of adulthood, which preceded marriage.[51] This is not to say that there were no women campaigning for the protection of their rights, the demand for equal pay in practice was one of the issues which saw thousands of women take to the streets in 1931.[52]

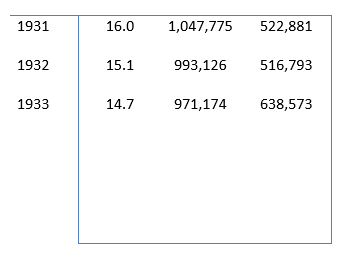

The vast majority of employed women in Weimar Germany would not have been impacted on by the ‘Law Governing the Legal Status of Female Civil Servants and Public Officials’ as much of women’s employment continued to be in traditional roles, such as nursing and dressmaking. Furthermore, the greater part of the female workforce were employed in family businesses, on farms, or worked in the household.[53] However, even women working in areas which were more traditionally female did not mean that their rights set out in the Weimar Constitution were respected. A greater number of women worked in agriculture than men by the mid-1920s. (see figure 2) Despite this, women were advised not to expect a management position in an agricultural career, as it would be resented by men. Instead, they were told to aim to work domestically or in an assistant role.[54]

Figure 2 Changing gender balance in agriculture[55]

When considering the activities of women in regard to protecting or furthering their working rights, it is important to understand the prevailing attitudes of women towards employment. The majority of conservative women saw the dominance of men in the workplace as a positive thing, believing that women’s natural place was in the household. The National Federation of German Housewives’ Associations (RDH) argued as early as WWI that housewifery should be recognised as a profession.[56] They argued that women and men were suited by nature to working in different areas and that the main consideration of women should be motherhood.

The idealised role of the Hausfrau was of great importance in the Weimar period. It formed the backbone of many of the policies of the various Womens’ Associations and influenced the way in which political parties tried to connect with female voters. It was not a role in which the equality desired by the Left held any place. Women had no legal control over any property that had been gained by either themselves or their husbands[57] and ideally had no use for equality in the workplace, as they spent their days in their home. The right-wing image of the Hausfrau was of a woman with no use for contraception, as she did her duty by having many children.

The ideal of a Hausfrau with many children fitted well with the desire to expand the population, a high population was linked to imperial ideas regarding the economy – the greater the population, the larger the economy, the more power a country could have.[58] This made the contraception issue one of great importance to both the left and the right of political opinion. The German birth control movement was one of the strongest in Europe. Helen Stöcker, left-wing leader of the Federation for the Protection of Mothers, argued that birth control should be legal for eugenic uses on the basis that “One will have to find means of preventing the incurably ill or degenerate from reproducing.”[59] This viewpoint was not unusual or purely German in a period when Social Darwinism was popular. Weismann’s theory of germ plasm was widely accepted and racial hygienists argued that, for the sake of the nation’s future, those with the ‘superior’ genes of the upper and middle classes should be producing the largest numbers of children.[60]

The government saw the ‘science’ of racial hygiene as an answer to the population problem, believing that it could remove the influence of less desirable genes which they associated with antisocial and ‘damaging’ elements of the populous.[61] The formation of a welfare state in which workers’ insurance, improved sanitation and a state vaccination policy had been among the policies, gave rise to the argument that natural selection had been stalled. Although there was a desperate perceived need to increase the population, for the sake of the economy the desire, as in various other countries, was a reduction in the numbers of people who could be dependent on the state.[62] With the economic troubles suffered in Weimar Germany concerns about ‘quality’ overtook the desire to increase the population. Such a desire is clear when looking at the willingness of the Reichstag to overrule Bavaria in 1922 when it tried to reintroduce legislation prohibiting the use of birth control.[63]

By the late 1920s popular opinion had moved significantly towards an acceptance of birth control, with Evangelical groups such as the United Evangelical Womens’ Federations of Germany arguing that contraception should be used if there were social or medical reasons which made childbirth undesirable.[64] That women were joining in a highly political issue and making arguments about the creation of families, which had traditionally been the decision of husbands, showed the extent to which women had become politicised on this particular issue. However, it should be considered that despite the emphasis on contraception to ‘improve’ the genetics of the nation, contraception was more easily available to the Mittlestand than the working classes, who were often unable to afford it where they had access to it. In addition to this, working class women were generally poorly educated about contraceptives.[65] The advertising and display of contraceptives was banned in Paragraph 184 of the penal code[66], leaving many working class women unable to access them.

Nonetheless, it is important that women were engaged in the contraception debate and that the use of contraceptives was protected by law throughout the Weimar Republic. The choice as to whether or not to become a mother, as well as to limit the number of pregnancies, was vital to women’s emancipation. Women who postponed childbirth would be able to work for longer, assuming they did not work for the government, and women with fewer children would have greater economic freedom. Contraception also enabled women to take greater control of their own health and bodies, with the avoidance of disease being as important as motherhood being a choice.

In the case of sexually transmitted diseases, radical women found themselves fighting alongside the more conservative with the dual goal of preventing infections such as gonorrhoea.[67] For the right contraceptives could be used to prevent the contraction of the disease, on the basis that it was difficult to detect, whereas on the left the issue was one of social hygiene. This is clear evidence that positive political change could happen for women, should there be a strong enough argument to convince the male dominated government.

An even more controversial issue than contraception that was vital to the emancipation of women was abortion. It was estimated that up to 800,000 abortions took place in Weimar Germany per year,[68] possibly rising to a million during the Depression.[69] This was a dramatic increase from the pre-war period, when it was estimated that there were 300,000 abortions per annum.[70] Due to the laws regarding abortion, it is difficult to know the exact numbers of women who underwent them and due to the basic nature of midwife training and the reluctance of some women to call a midwife, the numbers can only be approximate.[71]

Abortion was criminalised and carried a potential five year custodial sentence for any involved[72] under Paragraph 218 in German law, however, in common with most of Europe, abortion laws were difficult to police.[73] Abortions could be obtained illegally and the vast majority of women disagreed with the law. A Berlin newspaper which ran a poll on abortion law was inundated with almost half a million replies, of these only 150 were in favour of Paragraph 218.[74] Changing moral values had led to a greater frequency of extra-marital sex, which combined with issues surrounding contraception, resulted somewhat predictably in an increased rate of single motherhood.”[75] For the rich abortions could be obtained with a reasonable degree of safety and security from conviction, for poor women the only option was to see a back street abortionist,[76] leaving them more vulnerable to related complications and even death. In addition to this nearly all the 2,450 abortion related prosecutions in 1920 were of the working class.[77]

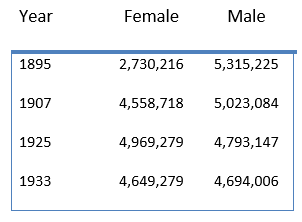

A high level of female involvement and influence in politics can be seen when examining the abortion issue, especially in relation to the extreme impact Paragraph 218 had on working class women. Artists, such as Käthe Kollwitz, and some political groups, such as the KPD, pushed for a repeal of Paragraph 218 of the criminal code in the early 1920s. Kollwitz argued that a woman should not be condemned to poverty by a lack of choice over motherhood and created a potent image of a starving mother and the children she was obliged by law to carry to term, should she fall pregnant (see figure 3[78]). This does not, however, take into account instances of women who were above the poverty line and having, or wishing to have, abortions.

Figure 3 KPD campaign poster for the repeal of article 218 of the criminal code

The KPD was not the only group arguing for a woman’s right to choose an abortion, the issue was also taken up by various elements of the arts. Kreuzzug des Weibes was released for the 1926/27 season and registered as the eighth most popular film of the year. It’s popularity prompted the release of various other German abortion films, as well as gaining distribution in the USA. [79] Usborne argues that the topicality of the film was a large factor in its success.[80] By this point the issue of abortion had become one of national concern,[81] with thousands of women of various political persuasions campaigning for a change in the law. With the economy in a vulnerable position, many families could not afford to have more children, the imagery of Kollwitz’s earlier campaign poster (see figure 3) was that of a stark reality for many.

Figure 5 Caricature of the ‘new woman’

The full force of the pro-abortion campaigns in which many women were involved can be seen in the changes in the law. In 1927 the Reichsgericht stated that therapeutic abortion could be justified by a doctor if the mother’s health or life were in danger and could only be preserved by abortion. It was only in this context that the “…right to life of the foetus is of lesser weight than the right of the mother…”[82] This is not to say that all women were working towards a common goal in regards to abortion, many women such as members and supporters of the Centre Party opposed abortion on religious grounds. The BDF, an otherwise influential group with thousands of female members, also rejected the arguments for abortion, believing that further provision of support for unwed mothers and the kinderreiche was the preferable way to tackle the issue of child poverty. As bearing an illegitimate child was more acceptable among the working classes than among the bourgeoisie,[83] this was a fairly radical stance for a Women’s Organisation to take. Given the right wing nature of the BDF it was not approval of extra marital sex that prompted this position.

Women and men on the right wing of politics also disapproved of the ‘new woman’ that had gained a presence in Weimar culture. The ‘new woman’ was young, employed, independent and had a much more open sexuality than her predecessors. She was frequently portrayed as ‘masculinised’ (see figure 5[84]) in her attire and personal habits, such as smoking. Despite her prominence in cultural mediums such as the cinema, the ‘new woman’ was largely a myth, based on white collar working women;[85] the majority of working women could not afford the lifestyle.[86]

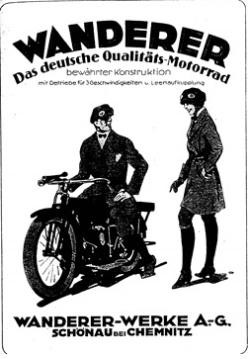

Figure 4 Motorbike advertisement showing the ‘new woman’

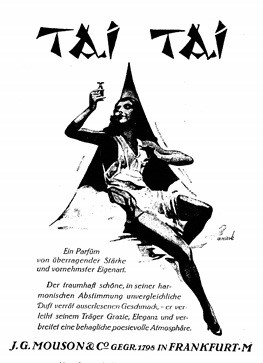

However, even if the majority of women had not adopted ‘masculine’ habits and though many of the single young working women did not have a vast surplus in their personal income, they did still have more spending power among them than previous generations. There were two and quarter million more women than men over the age of twenty in 1925, a consequence of this and the large number of widows, was that three quarters of the heads of single-head households in Germany were female.[87] A consequence of this was that a greater number of women would logically have been in complete control of the family finances, something which is clearly reflected in advertisements attempting to sell ‘masculine’ products, such as alcohol and motorbikes, to a female target audience. (see figures 4[88], 6[89] and 7[90]) Whilst the myth of the ‘new woman’ does not have any immediate connotations to women as a political force, the popularity of the myth and the existence of related advertising campaigns demonstrates that there must at least have been as desire for greater equality on the part of some women. Such a desire for emancipation is vital for it to occur and when considering the myth in relation to other important issues in Weimar it is clear that women had come a lot further along the road to equality than many of their European counterparts.

Figure 6 Advertisement, 1924

Figure 7 Brandy advertisement, 1924

Chapter Three – How the various parties mobilised and appealed (or not) to female voters; the women in the BDF: politics outside the parties

It is obvious even from a brief examination of political propaganda from Weimar Germany that the majority of parties attempted to engage women’s interest in their cause and to attract them as voters. Whether, like the KPD, they promoted full female equality, or like the NSDAP, were adamant that 111 women active in the Reichstag in 1920[91] should not be there, political parties in Weimar had to appeal to women. As the largest group in the country with the right to vote, women had become a key demographic.

The need to appeal to women extended further than their superiority in numbers; the majority of women presumably had no set political alliance at the start of the Weimar Republic, as they had no voting history. Parties on the left of politics felt they had the strongest appeal to female voters, as they consistently argued for the total emancipation of women. [92] Their founding members, notably including the female activist Rosa Luxemburg, held the value that “In all things… women are the equals of men”[93] as was set out in the ABC of Communism by Bukharin and Preobrazhensky.

The KPD were heavily involved in campaigning for the removal of Paragraph 218 from the penal code from early in the Weimar republic. One member of the KPD, an artist, Lex-Nerlinger, argued that women had a right to control their own bodies and should be able to decide if and when they wanted to bear children.[94] When considering the significance abortion has in relation to the emancipation of women in Weimar Germany, it is of great importance that the KPD decided to fight this issue, as it shows a recognition of female political concerns. That women were working at the forefront of the KPD’s campaign for abortion, shows the extent to which some far left women were involved in politics.

However, it is clear that although the KPD talked of the need to improve the lives of working women and to achieve the right to abortion, they regularly paid more attention to class in equality than women’s rights.”[95] In the eyes of the KPD gender considerations were bound with their overall objections to capitalist society and generally was not considered as an issue to be tackled within the legal structure of the Reichstag. This attitude can be seen in the Spartacus Manifesto, in which the only demand the Communists made was for the proletariat to rise internationally against class inequality.[96]

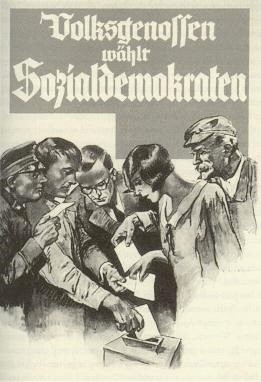

Figure 8 “People’s Comrades, Vote Social Democratic” SPD campaign poster, 1928

The SPD worked closely with the KPD on the abortion issue, the two parties presenting several bills to parliament together. [97] The party presented itself as a champion of women’s rights, working to attract female votes from across class boundaries. The SPD argued for the implementation of equal pay and access to education in addition to issues such as employment within the male dominated judiciary and the reform of marriage laws.[98] Their eagerness to promote their image as a woman-friendly party is reflected in propaganda, such as a 1928 campaign poster (see figure 8[99] ) which showed an image of the ‘new woman’ voting alongside men of various classes. It is clear from this poster that the SPD saw the support of women as important to maintaining their success. This is particularly significant because the SPD was the most popular party at the polls until 1932.

Despite the promotion of their woman-friendly image, it should be noted that the SPD were not always as progressive as they might seem at first glance. The SPD were not prepared to support equal pay for equal work in any meaningful way[100] and put great emphasis on motherhood as woman’s ultimate role. Although this attitude would appear to promote inequality, it is important to remember that many women still subscribed to the idealised role of the Hausfrau. In this way the SPD was actually fairly in touch with the values of many German women.

Figure 9 “Women! If you care for housing, prosperity, education, vote for the German Democrats!” DDP campaign poster, 1928

The German Democratic Party (DDP) was one of the more liberal parties which gained substantially from female votes in 1919.[101] However, support for the party waned after this point for the remainder of the Weimar Republic’s existence.[102] Its Protestant base was arguably a reason why it was unable to gain a broad female support base, as many Catholic women would have voted for the Centre Party, or if in Bavaria, the BVP (Bavarian People’s Party).

The DDP was aware of the need to attract female votes and as a ‘middle of the road’, fairly liberal party, it fully supported women’s right to vote and had a high proportion of professional, female politicians within its ranks.[103] Despite their lack of success with the electorate, the DDP did attempt to attract female voters with the use of propaganda. One campaign poster from 1928 (see figure 9[104]) targeted issues that were very much in the consciousness of the female electorate, as well as using the image of a traditional mother holding her child protectively. The image of mother and child implies that by voting for the DDP the German mother would be caring for her offspring and protecting their future.

Figure 10 “Provide for our future – vote Centre” Centre Party campaign poster, 1928

The DDP was not the only party to attempt to win the female vote by campaigning with potent, maternal imagery. In one of their posters from 1928 (see figure 10[105]) the Centre Party displayed an image of a mother and her baby, with a cross dominating the background. It is a clear reference to the Virgin Mary and her baby Jesus, an obvious indication of the party’s Catholic values as well as promoting the ideal of motherhood. The accompanying slogan, “provide for our future”, was an adoption of the same tactic being used by the DDP in trying to attract women by suggesting the protection of the best interests of their children.

As a Catholic organisation, the Centre Party was anti-abortion and anti-contraception, believing firmly that abortion was a sin prohibited in the fifth commandment and that contraception violated the instruction of verses 8-10 in Genesis. This opinion was enshrined in the 1930 encyclical by the Pope.[106] In this way the Centre Party can be said to differ from more left wing parties when it came to attracting women, as they openly opposed the mass demand for abortion. Whilst this would have been supported by the majority of Catholic women, it is clear that religious beliefs took precedence to women’s rights in the Centre Party.

Figure 11 “We hold fast to the word of God! Vote German Nationalist” DNVP campaign poster ca. 1930

The emphasis on religion in relation to women’s rights was a priority of right wing Protestant groups, as well as the Centre Party. It is clear in the 1930 DNVP campaign poster (see figure 11[107]) that religion was a major factor in their perception of women. The use of the two female relations and the slogan “we hold fast to the word of God” suggests that women would be behaving morally by voting for the DNVP on the basis that religion overcut all other political concerns. The image is from a painting dated to 1889,[108] the use of which places a heavy emphasis on German tradition.

Both the DNVP and the DVP held to traditional ideas in relation to women at work. They believed that women should be employed in ‘feminine’ jobs, but should preferably aspire to the role of Hausfrau. Although some female members ostensibly worked for women’s rights, their insistence on the restriction of female employment restricted the demographics to which they were able to appeal.[109] This did not restrict their support base as greatly as it would in a current context, as the belief that suffrage had given women the equality to which they were entitled was widely held.[110] Right wing women made it clear that “…only the thought of the Volksgemeinschaft and the damage that has to be repaired urges woman to leave her narrow private sphere. This is not at all a question of women’s rights…”[111]

Recognition of the importance of female support and the range of female activity can be seen in these right wing parties sending women to address female, Protestant groups regarding topics as varied as the occupation of the Ruhr and the protection of Deutschtum, (which they considered to be defined by Protestant, bourgeoisie values and their social and economic status).[112] By actively approaching women and appealing to them on the basis of widely held, traditional values, they were able to garner much greater support than parties such as the SPD.

The DNVP and DVP did not hold as strictly to their values as the Centre Party, however, being prepared to sacrifice some parts of their ideology in order to promote what they saw as the good of the nation. Although they saw the birth of illegitimate children as immoral on the basis of it being a perceived violation of the sanctity of marriage, they were so concerned about the falling birthrate that they pushed for the improvement of support for unwed mothers. However, they kept to their ideology in insisting that the illegitimate child had a lower social status than the legitimate child.[113]

The national birthrate and the family were two of the major interests for women working within the DNVP and the DVP. They advocated support for kinderreiche families, regardless of their income, yet at the same time opposed the state intervention generally advocated by the Left on many political matters.[114]

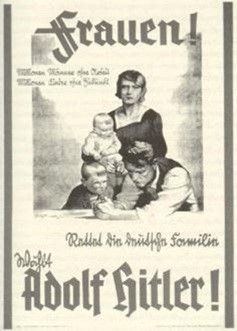

Figure 12 “Women! Millions of men without jobs, millions of children with no future. Save the German family. Vote Adolf Hitler!” NSDAP campaign poster, 1932

The willingness to promote aspects of welfare policy in order to further their own ideological aims was not a trait often shared by the far right, nonetheless the NSDAP prevaricated about their attitude towards women when questioned by those they felt would disapprove. In 1932 Gregor Straßer stated that “the working woman has equality of status in the National Socialist State, and has the same right to security as the married woman and mother.”[115] However, when in a secure setting the party was very clear on their ideology regarding women. The speech delivered by Hitler to an audience of women at the Nuremburg Parteitag in 1934 argued that women and men belonged, by nature, to two different spheres of life. He claimed that the NSDAP showed women the respect they were due by valuing their God-given place in the home and as mothers. A woman’s battle was childbirth, “…a battle waged for the existence of her people.”[116] Hitler claimed that the NSDAP protested against the inclusion of women in political life on the basis that the idea of equality through “…the overlapping spheres of activity of the sexes…”[117] was a “…corrupted intellectualism which will put asunder that which God hath joined.”[118]

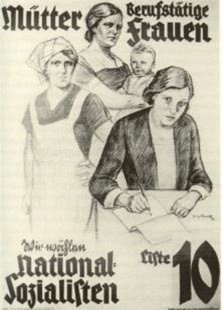

Figure 13 “Mothers, Working Women. We vote National Socialist List 10” NSDAP campaign poster 1928

Regardless of their extreme ideology and their reluctance to allow any influential roles within their party to be held by women,[119] the NSDAP clearly recognised the advantages of releasing female-specific propaganda. Like many other parties they targeted women with campaign posters (see figures 12[120] and 13[121]). In both posters the Hausfrau is shown as a solemn and strong figure, holding her child close to her. Like other parties, the NSDAP uses such imagery and the accompanying slogans to present itself as the protector of families, an issue of great importance in a myriad of ways to the Weimar public.

In addition to attempting to engage with women in regard to motherhood, figure 13 also addresses women who are in employment, although figure 12, produced four years later, refers to employment only in regard to men. This reflects the confidence of the NSDAP at this juncture, with an ever increasing support base they could concentrate on their ideology of the woman as Hausfrau.

In addition to working within the political parties, many women joined Women’s Associations. These were running during the nineteenth century, becoming so popular that the Bund Deutsher Frauenverine (BDF) was formed in 1894 under the leadership of Marianne Weber, Helene Langer and Gertrud Bäumer. At the advent of WWI the BDF had a membership of around 300,000 women. After the war the focus of the BDF was on the promotion and organisation of kindergartens, homes and recreational centres for unmarried mothers and educational reform.[122] Despite having these goals in common with the left of politics, the BDF was generally conservative in sexual and family matters. This trend within the movement lead to them rejecting demands for government support for unmarried mothers and legal abortion.[123]

The RDH and the National Federation of Agricultural Housewives’ Associations (RLHV) were two of the largest organisations with BDF membership. As their names would suggest, their interests were in representing and improving life for women in their traditional role in the home.[124] In addition to this the Bund für Mutterschutz (League for the Protection of Mothers), run by Helen Stöker had also had membership.[125] Despite their vast numbers, the BDF was less political than the socialist women’s movement.[126]

Although they had a strong stance on issues such as abortion, the BDF held to the principle of Überparteilichkeit, neutrality in political matters. Despite this hindrance and the need to avoid a split with the housewives’ leagues the BDF did recommend to their supporters as much as they could to beware “…revolution, hate, and blind passion”, which Reagin argues can be deciphered as a vague warning against parties such as the NSDAP.[127] In addition to this, in 1932, the BDF appealed to all parties to respect the political rights of women.[128] It is in the context of trying to influence their members that the BDF were least successful in their attempt to be a political force. Although they were able to appeal to women on a variety of issues, their attempts to influence society were not through direct politics. This does not make them any less significant a presence in Weimar, as they were active in society, often providing mothers with practical support such as kindergartens.

Conclusion

It is clear that women were a political force in Weimar Germany, however it is also clear that they were far from being on equal terms with men. Despite having political and employment rights enshrined in the Weimar Constitution, women frequently found themselves subject to discriminatory treatment. Wages and salaries were unequal, with women being paid less than men as a rule. In addition to this women did not have legal control over their own bodies in regard to childbearing. Contraception was frequently unavailable to working class women, many of whom did not even know how to use or obtain it due to a poor education.

Many of the political parties were run by men and held to the image of the Hausfrau as the ideal role for all women. However, women created their own role in politics through Women’s Associations unrelated to particular parties. With important issues, such as abortion, women proved themselves to be a massive political force by campaigning and taking to the streets in their thousands, demanding changes to the law. Although the Reichstag was run almost entirely by men and there was fierce opposition to the legalisation of abortion, the pro-abortion campaigners, including many women, obtained women the right to an abortion should be necessary to prevent their demise. Although this was far from being the liberal law that many had worked for, it was a very important change and evidence of the extent to which women truly could be a political force in Weimar Germany.

Although the change to the abortion law was only one of the many areas in which progress was required in Weimar Germany to achieve a form of female emancipation which would be recognised today, it is vital to remember the context in which women were working. Radical women such as Rosa Luxemburg may have demanded full equality with men, but thousands of German women did not perceive this as a desirable aspiration. If emancipation is relative to the demands of women, it is clear that for many women it had been achieved and that they were therefore the maximum political force that they wanted to be.

For more left-wing women, however, there was a desire to expand their political influence. Women on the far right in particular wanted full legal equality. Although they did not achieve this during the Weimar years, their presence in the republic was important both as campaigners and at the polls.

This study has brought together an overview of various facets of the ‘woman question’ in Weimar Germany and made some attempt to understand the female presence in social politics. However, this question has a long and complicated answer which has yet to fully develop into a complete and fascinating historiography. The variety of opinions, methods of involvement in politics and the strict class differences between the women of Weimar Germany make them a political force of great complexity.

Bibliography

Primary Sources

Museums:

KPD poster for the cancellation of article 218 of the criminal code, designed by Käthe Kollwitz, photo taken of original document stored in the Deutsches Historisches Museum, Berlin, January 2011

Online collections:

Article 109 of the Reich Constitution of 11th August 1919 (Weimar Constitution) with Modifications (1) http://www.zum.de/psm/weimar/weimar_vve.php#Basic rights and obligations of the Germans

Published:

Luxemburg, Rosa, “Letters to Leo Jogiches” in Comrade and Lover: Rosa Luxemburg’s Letters to Leo Jogiches, ed.Elzbieta Ettinger, (Cambridge, 1979

“Paragraph 218: A Modern Gretchen Tragedy”, in The Weimar Republic Sourcebook, ed. Kaes, Anton, Jay, Martin and Dimendberg, Edward, (University of California Press, California, 1994)

“Caricature spoofing the ‘masculinization’ of the 1920s woman, 1925” in Nazi Chic? Fashioning Women in the Third Reich, Guenther, Irene, (Berg, Oxford, 2004) plate 5

“Motorcycle advertisement, 1923” in Women and Modernity in Weimar Germany: Reality and Representation in Popular Fiction, Petersen, Vibeke Rützou, (Berghahn Books, Oxford, 2001)

“J. G. Mouson and Co, Gegr. 1798 in Frankfurt. M,” in Women and Modernity in Weimar Germany: Reality and Representation in Popular Fiction, Petersen

“Brandy advertisement showing a femme fatale plying a tiny, formally-dressed (male) bird with alcohol” in Women and Modernity in Weimar Germany: Reality and Representation in Popular Fiction, Petersen

“Spartacus Manifesto”, in The Weimar Republic Sourcebook, ed. Kaes, Anton, Jay, Martin, Dimendburg, Edward, (University of California Press, California, 1994)

“SPD campaign poster, 1928” in Winning women’s votes: propaganda and politics in Weimar Germany, Sneeringer, (University of North Carolina Press, North Carolina, USA, 2002)

“DDP campaign poster, 1928” in The Politics of the Body in Weimar Germany, Usborne, table 6

“Centre Party campaign poster, 1928” in Winning Women’s Votes: propaganda and politics in Weimar Germany, Sneeringer

“DNVP campaign poster, ca. 1930” in Weimar Germany: Promise and Tragedy, Weitz

“ Magdalene von Tiling, DNVP” in , Mothers of the Nation: Right Wing Women in Weimar Germany, Schek

“Gregor Straße” in German Women and the Triumph of Hitler, Evans, Richard J., (The Journal of Modern History, Vol. 48, No. 1, On demand Supplement, The University of Chicago Press, March 1976)

“Hitler’s speech to women at the Nuremburg Parteitag” in The Speeches of Adolf Hitler, April 1922 – August 1939: An English translation of representative passages arranged under subjects, ed. Baynes, Norman H., (Oxford University Press, London, 1942)

“NSDAP campaign poster, 1932” in Winning Women’s Votes: propaganda and politics in Weimar Germany, Sneeringer

“NSDAP campaign poster, 1928” in Winning Women’s Votes: propaganda and politics in Weimar Germany, Sneeringer

Secondary sources

Books

Petersen, Vibeke Rützou, Women and Modernity in Weimar Germany: Reality and Representation in Popular Fiction, (Berghahn Books, USA, 2001)

Kitson, Alison, Germany, 1858-1990: hope, terror and revival, (Oxford University Press, Oxford, 2001)

Sneeringer, Julia, Winning women’s votes: propaganda and politics in Weimar Germany, (University of North Carolina Press, North Carolina, USA, 2002)

Scheck, Raffael, Mothers of the Nation: Right Wing Women in Weimar Germany, (Berg, Oxford, 2004)

Weitz, Eric D., Creating German Communism, 1890-1990: from popular protests to socialist state, (Princeton University Press, Princeton, New Jersey, 1997)

Bukharin and Preobrazhensky, The ABC of Communism, (Penguin Books Ltd, Middlesex, England, 1969 (translation of original text from 1922)

Ed. Kaes, Anton, Jay, Martin, Dimendberg, Edward, The Weimar Republic Sourcebook, (University of California Press, California, 1994)

Mazower, Mark, Dark Continent, (Penguin Books, London, 1999) p78

Grunberger, Richard, A Social History of the Third Reich, (Cox and Wyman Ltd, London, 1971

Fest, Joachim C., The Face of the Third Reich, (Penguin Books, London, 1970 – translated from the 1963 publication in German, R. Piper, Munich)

Usborne, Cornelie, The Politics of the Body in Weimar Germany, (Macmillan, England, 1992)

Elzbieta Ettinger (ed.), Comrade and Lover: Rosa Luxemburg’s Letters to Leo Jogiches (Cambridge, 1979)

Woycke, James, Birth Control in Germany 1871-1933, (Routledge, London, 1988)

Baynes, Norman H., The Speeches of Adolf Hitler, April 1922 – August 1939: An English translation of representative passages arranged under subjects, (Oxford University Press, London, 1942)

Pauwels, Jaques R., Women, Nazis, and Universities: Female University Students and the Third Reich, 1933-1945, (Greenwood Press, London, 1984)

Frölich, Paul, Rosa Luxemburg: Her life and work, (Howard Fertig, Inc., New York, 1969)

Reagin, Nancy Ruth, A German women’s movement: class and gender in Hanover, 1880-1933, (The University of North Carolina Press, USA, 1995)

Freidman, Matthew J., Keane, Terence M., Resick, Patricia A., Handbook of PTSD: Science and Practice, (The Guilford Press, New York, 2007)

Ed. Bridenthal, Renate, Grossman, Atina and Kaplan, Marion, When Biology Became Destiny: Women in Weimar and Nazi Germany, (Monthly Review Press, New York, 1984)

Weitz, Eric D., Weimar Germany: Promise and Tragedy, (Princeton University Press, Princeton, 2007)

Peukert, Detlev J. K., The Weimar Republic: The Crisis of Classical Modernity, (Hill and Wang, New York, 1992

Bock, Gisela, Women in European History, (Blackwell Publishers Ltd, Oxford, 2002)

Bookbinder, Paul, Weimar Germany: The Republic of the Reasonable, (Manchester University Press, Manchester, 1996)

Journals

Evans, Richard J., German Women and the Triumph of Hitler, (The Journal of Modern History, Vol. 48, No. 1, On demand Supplement, The University of Chicago Press, March 1976)

Usborne, Cornelie, Rebellious Girls and Pitiable Women: Abortion Narratives in Weimar Popular Culture, (Oxford Journals, Humanities, German History, Vol. 23, Issue 3, July 2005)

Honeycutt, Karen, Socialism and Feminism in Imperial Germany, (Signs, Vol. 5, No. 1, Women in Latin America, The University of Chicago Press, Autumn, 1979)

Evans, Richard J., German Social Democracy and Women’s Suffrage 1891-1918, (Journal of Contemporary History, Vol. 15, No. 3, Sage Publications Ltd, July 1980)

Bridenthal, Renate, Beyond Kinder, Küche, Kirche: Weimar Women at Work, (Central European History, Vol. 6, No. 2, Cambridge University Press, June 1973)

Websites

Billings, Molly, The Influenza Pandemic of 1918, (Stanford University, USA, 2005) – http://virus.stanford.edu/uda/ – last accessed 30th April 2011

[1] Article 109 of the Reich Constitution of 11th August 1919 (Weimar Constitution) with Modifications (1) http://www.zum.de/psm/weimar/weimar_vve.php#Basic rights and obligations of the Germans

[2] Evans, Richard J., German Women and the Triumph of Hitler, (The Journal of Modern History, Vol. 48, No. 1, On demand Supplement, The University of Chicago Press, March 1976) pp125-126

[3] Fest, Joachim C., The Face of the Third Reich, (Penguin Books, London, 1970 – translated from the 1963 publication in German, R. Piper, Munich) p401

[4] Fest, The Face of the Third Reich, p401

[5] Fest, The Face of the Third Reich, p401

[6] Grunberger, Richard, A Social History of the Third Reich, (Cox and Wyman Ltd, London, 1971) p266

[7] Sneeringer, Julia, Winning women’s votes: propaganda and politics in Weimar Germany, (University of North Carolina Press, North Carolina, USA, 2002) p3

[8]Billings, Molly, The Influenza Pandemic of 1918, (Stanford University, USA, 2005) http://virus.stanford.edu/uda/

[9] Bridenthal, Renate, Grossman, Atina and Kaplan, Marion (ed.), When Biology Became Destiny: Women in Weimar and Nazi Germany, (Monthly Review Press, New York, 1984) pp179-180

[10] Luxemburg, Rosa, “Letters to Leo Jogiches” in Comrade and Lover: Rosa Luxemburg’s Letters to Leo Jogiches, ed.Elzbieta Ettinger, (Cambridge, 1979)p39

[11] Frölich, Paul, Rosa Luxemburg: Her life and work, (Howard Fertig, Inc., New York, 1969) pp253-255

[12] Luxemburg ‘Letters to Leo Jogiches’ p3

[13] Luxemburg ‘Letters to Leo Jogiches’) p xx

[14] Frölich, Rosa Luxemburg: Her life and work, pp251-252

[15]Luxemburg ‘Letters to Leo Jogiches’ p12

[16] Luxemburg ‘Letters to Leo Jogiches’ pp xxvii-xxviii

[17]Luxemburg ‘Letters to Leo Jogiches’ pp xxviii- xxix

[18] Frölich, Rosa Luxemburg: Her life and work, p256

[19] Sneeringer, Winning women’s votes: propaganda and politics in Weimar Germany, p4

[20] Honeycutt, Karen, Socialism and Feminism in Imperial Germany, (Signs, Vol. 5, No. 1, Women in Latin America, The University of Chicago Press, Autumn, 1979) p33

[21] Evans, Richard J., German Social Democracy and Women’s Suffrage 1891-1918, (Journal of Contemporary History, Vol. 15, No. 3, Sage Publications Ltd, July 1980) p535

[22] Honeycutt, Socialism and Feminism in Imperial Germany, p34

[23] Evans, German Social Democracy and Women’s Suffrage 1891-1918, p536

[24] Evans, German Social Democracy and Women’s Suffrage 1891-1918, p536

[25] Ibid. p356

[26] Ibid. pp356-357

[27] Sneeringer, Winning women’s votes: propaganda and politics in Weimar Germany, p1

[28] Evans, German Social Democracy and Women’s Suffrage 1891-1918, p533

[29] Mazower, Mark, Dark Continent, (Penguin Books, London, 1999) p80

[30] Mazower, Dark Continent, p82

[31] Ibid. pp78 – 80

[32] Pauwels, Jaques R., Women, Nazis, and Universities: Female University Students and the Third Reich, 1933-1945, (Greenwood Press, London, 1984) p144

[33] Mazower, Dark Continent, p78

[34] Ibid. p78

[35] Mazower, Dark Continent, p80

[36] Freidman, Matthew J., Keane, Terence M., Resick, Patricia A., Handbook of PTSD: Science and Practice, (The Guilford Press, New York, 2007)pp 21-22

[37] Freidman, Matthew, et al, Handbook of PTSD: Science and Practice, pp21-22

[38] Mazower, Dark Continent, p78

[39] Ibid. pp 80-81

[40] Ibid. p81

[41] Ibid. p81

[42] Ibid. p81

[43] Ibid. p82

[44] Peukert, Detlev J. K., The Weimar Republic: The Crisis of Classical Modernity, (Hill and Wang, New York, 1992 p97

[45] Peukert, The Weimar Republic: The Crisis of Classical Modernity, p96

[46] Weitz, Eric D., Weimar Germany: Promise and Tragedy, (Princeton University Press, Princeton, 2007) p157

[47] Peukert, The Weimar Republic: The Crisis of Classical Modernity, p97

[48] Ibid. p96

[49] Ibid. p97

[50] Ibid. p97

[51] Ibid. p97

[52] Bridenthal, Renate, et al (ed.), When Biology Became Destiny: Women in Weimar and Nazi Germany, p67

[53] Peukert, The Weimar Republic: The Crisis of Classical Modernity, p98

[54] Bridenthal, Renate, Beyond Kinder, Küche, Kirche: Weimar Women at Work, (Central European History, Vol. 6, No. 2, Cambridge University Press, June 1973) p154

[55] Bridenthal, Beyond Kinder, Küche, Kirche: Weimar Women at Work, p151

[56] Bridenthal, Renate, et al (ed.), When Biology Became Destiny: Women in Weimar and Nazi Germany, p155

[57] Bridenthal, Beyond Kinder, Küche, Kirche: Weimar Women at Work, p151

[58] Usborne, Cornelie, The Politics of the Body in Weimar Germany, (Macmillan, England, 1992) p3

[59] Mazower, Dark Continent, p87

[60] Usborne, The Politics of the Body in Weimar Germany, pp4-5

[61] Ibid. p5

[62] Ibid. p5

[63] Ibid. p103

[64] Ibid. p104

[65] Petersen, Vibeke Rützou, Women and Modernity in Weimar Germany: Reality and its Representation in Popular Fiction, (Berghahn Books, Oxford, 2001) p32

[66] Bridenthal, Renate, et al (ed.), When Biology Became Destiny: Women in Weimar and Nazi Germany, p68

[67] Usborne, The Politics of the Body in Weimar Germany, pp110-111

[68] Mazower, Dark Continent, p86

[69] Woycke, James, Birth Control in Germany 1871-1933, (Routledge, London, 1988) p68

[70] Ibid. p68

[71] Ibid. p68

[72] “Paragraph 218: A Modern Gretchen Tragedy”, in The Weimar Republic Sourcebook, ed. Kaes, Anton, Jay, Martin and Dimendberg, Edward, (University of California Press, California, 1994) pp 202-203

[73] Mazower, Dark Continent, p85

[74] Petersen, Women and Modernity in Weimar Germany: Reality and its Representation in Popular Fiction, p33

[75] Ibid. p26

[76] Ibid. p32

[77] Ed. Kaes, Anton, Jay, Martin and Dimendberg, Edward, The Weimar Republic Sourcebook, (University of California Press, California, 1994) p202

[78] KPD poster for the cancellation of article 218 of the criminal code, designed by Käthe Kollwitz, photo taken of original document stored in the Deutsches Historisches Museum, Berlin, January 2011

[79] Usborne, Cornelie, Rebellious Girls and Pitiable Women: Abortion Narratives in Weimar Popular Culture, (Oxford Journals, Humanities, German History, Vol. 23, Issue 3, July 2005) p325

[80] Usborne, Rebellious Girls and Pitiable Women: Abortion Narratives in Weimar Popular Culture, p325

[81] Bridenthal, Renate, et al (ed.), When Biology Became Destiny: Women in Weimar and Nazi Germany, p68

[82] Woycke, James, Birth Control in Germany 1871-1933, (Routledge, London, 1988)p72

[83] Petersen, Women and Modernity in Weimar Germany: Reality and its Representation in Popular Fiction, p27

[84] “Caricature spoofing the ‘masculinization’ of the 1920s woman, 1925” in Nazi Chic? Fashioning Women in the Third Reich, Guenther, Irene, (Berg, Oxford, 2004) plate 5

[85] Peukert, The Weimar Republic: The Crisis of Classical Modernity, p98

[86] Peukert, The Weimar Republic: The Crisis of Classical Modernity, p100

[87] Petersen, Women and Modernity in Weimar Germany: Reality and its Representation in Popular Fiction, p19

[88] “Motorcycle advertisement, 1923” in Women and Modernity in Weimar Germany: Reality and Representation in Popular Fiction, Petersen, Vibeke Rützou, (Berghahn Books, Oxford, 2001) pxiii

[89] “J. G. Mouson and Co, Gegr. 1798 in Frankfurt. M,” in Women and Modernity in Weimar Germany: Reality and Representation in Popular Fiction, Petersen, pxii

[90] “Brandy advertisement showing a femme fatale plying a tiny, formally-dressed (male) bird with alcohol” in Women and Modernity in Weimar Germany: Reality and Representation in Popular Fiction, Petersen, pxi

[91] Kitson, Alison, Germany, 1858-1990: hope, terror and revival, (Oxford University Press, Oxford, 2001) p1928

[92] Weitz, Eric D., Creating German Communism, 1890-1990: from popular protests to socialist state, (Princeton University Press, Princeton, New Jersey, 1997) p188

[93] Bukharin and Preobrazhensky, The ABC of Communism, (Penguin Books, England, 1969) (translation of original text from 1922) p227

[94] Bridenthal, Renate, et al (ed.), When Biology Became Destiny: Women in Weimar and Nazi Germany, p67

[95] Ed. Kaes, Anton, Jay, Martin, Dimendberg, Edward, The Weimar Republic Sourcebook, (University of California Press, California, 1994) p195

[96] “Spartacus Manifesto”, in The Weimar Republic Sourcebook, ed. Kaes, Anton, Jay, Martin, Dimendburg, Edward, (University of California Press, California, 1994) pp37-38

[97] Scheck, Raffael, Mothers of the Nation: Right Wing Women in Weimar Germany, (Berg, Oxford, 2004) p87

[98]Sneeringer, Winning women’s votes: propaganda and politics in Weimar Germany, pp94-96

[99] “SPD campaign poster, 1928” in Winning women’s votes: propaganda and politics in Weimar Germany, Sneeringer, (University of North Carolina Press, North Carolina, USA, 2002) p125

[100] Ed. Kaes, Anton, Jay, Martin, Dimendberg, Edward, The Weimar Republic Sourcebook, (University of California Press, California, 1994) p195

[101] Bock, Gisela, Women in European History, (Blackwell Publishers Ltd, Oxford, 2002) p153

[102] Bookbinder, Paul, Weimar Germany: The Republic of the Reasonable, (Manchester University Press, Manchester, 1996) p48

[103] Weitz, Weimar Germany: Promise and Tragedy, p88

[104] “DDP campaign poster, 1928” in The Politics of the Body in Weimar Germany, Usborne, table 6

[105] “Centre Party campaign poster, 1928” in Winning Women’s Votes: propaganda and politics in Weimar Germany, Sneeringer, p151

[106] Usborne, The Politics of the Body in Weimar Germany, p176

[107] “DNVP campaign poster, ca. 1930” in Weimar Germany: Promise and Tragedy, Weitz, p95

[108] Weitz, Weimar Germany: Promise and Tragedy, p95

[109] Scheck, Mothers of the Nation: Right Wing Women in Weimar Germany, p65

[110] Ibid. p65

[111] “ Magdalene von Tiling, DNVP” in , Mothers of the Nation: Right Wing Women in Weimar Germany, Schek, p65

[112] Reagin, Nancy Ruth, A German women’s movement: class and gender in Hanover, 1880-1933, (The University of North Carolina Press, USA, 1995) p234

[113] Scheck, Mothers of the Nation: Right Wing Women in Weimar Germany, p87

[114] Ibid. pp86-87

[115] “Gregor Straße” in German Women and the Triumph of Hitler, Evans, Richard J., (The Journal of Modern History, Vol. 48, No. 1, On demand Supplement, The University of Chicago Press, March 1976) p138 reference 43

[116] “Hitler’s speech to women at the Nuremburg Parteitag” in The Speeches of Adolf Hitler, April 1922 – August 1939: An English translation of representative passages arranged under subjects, ed. Baynes, Norman H., (Oxford University Press, London, 1942) pp 528-529

[117] “Hitler’s speech to women at the Nuremburg Parteitag” in The Speeches of Adolf Hitler, April 1922 – August 1939: An English translation of representative passages arranged under subjects, ed. Baynes, Norman H., (Oxford University Press, London, 1942) p529

[118] “Hitler’s speech to women at the Nuremburg Parteitag” in The Speeches of Adolf Hitler, April 1922 – August 1939: An English translation of representative passages arranged under subjects, ed. Baynes, Norman H., (Oxford University Press, London, 1942) p529

[119] Evans, German Women and the Triumph of Hitler, p140

[120] “NSDAP campaign poster, 1932” in Winning Women’s Votes: propaganda and politics in Weimar Germany, Sneeringer, p241

[121] “NSDAP campaign poster, 1928” in Winning Women’s Votes: propaganda and politics in Weimar Germany, Sneeringer, p161

[122] Ed. Kaes, Anton et al, The Weimar Republic Sourcebook, p195

[123] Ed. Kaes, Anton et al, The Weimar Republic Sourcebook, p195

[124] Bridenthal, Renate, et al (ed.), When Biology Became Destiny: Women in Weimar and Nazi Germany, p154

[125] Ed. Kaes, Anton et al, The Weimar Republic Sourcebook, p195

[126] Ibid. p195

[127] Reagin, Nancy Ruth, A German women’s movement: class and gender in Hanover, 1880-1933, (The University of North Carolina Press, USA, 1995) p242

[128] Ibid. p243